Guy says women who have given birth don’t understand biology, and in evidence offers a smug smart-ass young man in…a Youtube video.

That’s women told.

Guy says women who have given birth don’t understand biology, and in evidence offers a smug smart-ass young man in…a Youtube video.

That’s women told.

Another contrarian slams the door:

Boris Johnson’s top policy aide has quit over the PM’s false claim that Sir Keir Starmer failed to prosecute serial sex offender Jimmy Savile when he was director of public prosecutions.

…

Munira Murza said the PM he should have apologised for the misleading remarks.

In her resignation letter, published by The Spectator, she wrote: “You are a better man than many of your detractors will ever understand, which is why it is so desperately sad that you let yourself down by making a scurrilous accusation against the leader of the opposition.”

What’s funny about this is who she is.

Mirza, who quit over Boris Johnson’s false claim that Keir Starmer held back attempts to prosecute Jimmy Savile, was the official behind Downing Street’s much criticised report into racial disparities, which downplayed structural factors.

Contrarian, you see.

Her political journey has certainly been a long one. Born in Oldham in 1978 to parents who came to the UK from Pakistan, she went to her local comprehensive school and Oldham sixth form college before studying English at Mansfield College, Oxford.

Unlike Johnson, who was president of the Oxford Union and involved in Tory politics, Mirza was a student radical, becoming a member of the Revolutionary Communist party, contributing to its magazine Living Marxism.

There it is. She’s part of the RCP/Spiked crowd! The contrariest contrarians of all time, who turned as one from the RCP to…the Spiked tendency.

Labour woman MP says what now?

But…he doesn’t, does he. He didn’t. That’s the point, surely. Not that “if he did, he would be,” but that “He didn’t, because that’s not how this works.” Raping and murdering women is about women, it’s not about women and men who pretend to be women. What the Wayne Couzenses and the Peter Sutcliffes and the rest of them hate is women, not women and men who wear makeup.

How can Stella Creasy not understand that?

Men stealing women’s athletic prizes – cool, or no?

Less than two days after several members of the University of Pennsylvania women’s swimming team released a letter in support of Lia Thomas, 16 team members and their families responded with a letter of their own. This letter, directed to the University of Pennsylvania and the Ivy League, requested that school and conference do not engage in litigation following USA Swimming’s release of its new transgender-inclusion policy.

The letter was sent to the University of Pennsylvania and the Ivy League by three-time Olympic champion Nancy Hogshead-Makar, who is the CEO of Champion Women. Hogshead-Makar has been a longtime advocate of women’s rights and has fought for equal opportunity for women’s athletes. During the Lia Thomas debate, Hogshead-Makar has repeatedly noted the unfair advantages of Thomas as a transgender woman when competing against biological females.

So there’s disagreement among the swimmers about the fairness of Lia Thomas’s con game.

We fully support Lia Thomas in her decision to affirm her gender identity and to transition from a man to a woman. Lia has every right to live her life authentically.

Or to put it another way, we don’t care what Thomas does with his “gender” in his private life.

However, we also recognize that when it comes to sports competition, that the biology of sex is a separate issue from someone’s gender identity. Biologically, Lia holds an unfair advantage over competition in the women’s category, as evidenced by her rankings that have bounced from #462 as a male to #1 as a female. If she were to be eligible to compete against us, she could now break Penn, Ivy, and NCAA Women’s Swimming records; feats she could never have done as a male athlete.

I will never understand why the grotesque unfairness of this isn’t so blindingly obvious to everyone that it just can’t get off the ground.

We have dedicated our lives to swimming. Most of us started the same time Lia did, as pre-teens. We have trained up to 20 hours a week, swimming miles, running and lifting weights. To be sidelined or beaten by someone competing with the strength, height, and lung capacity advantages that can only come with male puberty has been exceedingly difficult.

Because it’s so unfair, and so obviously unfair, yet grown-ass adults are forcing it on us. Exceedingly difficult indeed.

We have been told that if we spoke out against her inclusion into women’s competitions, that we would be removed from the team or that we would never get a job offer. When media have tried to reach out to us, these journalists have been told that the coaches and athletes were prohibited from talking to them. We support Lia’s mental health, and we ask Penn and the Ivy League to support ours as well.

You know, from the outside, Lia’s mental health looks pretty damn robust. He seems very cheerful, not to say triumphant and smug.

On the recent statements published by the Equality and Human Rights Commission on the governments’ consultation on conversion therapy, Amnesty International UK disagree unreservedly in the EHRC’s assessment of separating protections for LGBTI people and specifically excluding trans people from initial legislation.

These statements are actively damaging to the rights of trans and non-binary people in the UK, and we find them to be disappointing and deeply troubling.

Emphasis very much theirs.

But what are these rights? What are these rights that trans and non-binary people have that mustn’t be separated from the rights that lesbian and gay people have? Amnesty UK of course doesn’t say. It doesn’t even mention. We’re just supposed to know.

Nor does Amnesty UK explain how it damages the rights of trans people to talk about them separately from those of lesbian and gay people. Again we’re just supposed to know.

And that’s a problem, because sometimes some claimed “rights” of trans people encroach on the rights of lesbian and gay people. Bullying lesbians who don’t want to couple up with men who identify as lesbians, for instance – there’s a place where the rights of lesbians clash with the putative rights of men who identify as lesbians. I say “putative” because I don’t think men who identify as lesbians have any right to bully lesbians, or demand “validation” from them, let alone any right to order lesbians to have sex with them.

So what rights are we talking about here? Why doesn’t Amnesty UK spell out exactly what those rights are? Why does it just repeat formulaic guff about “protections for LGBTI people” and leave it at that?

Probably because it knows that spelling out “trans lesbians have the right to demand sex from lesbians” would look a bit off.

We encourage the UK and Scottish Governments’ to continue to show commitment and leadership on human rights by delivering on their commitments to reforming the Gender Recognition Act and introducing a comprehensive legislative ban on conversion therapy that protects the whole of the LGBTI community, including those who are trans and non-binary

But “conversion therapy” for lesbian and gay people is not the same thing, or the same kind of thing, as asking questions before agreeing with people who claim to be the opposite sex. There are many differences. To take the most obvious: lesbians and gay people don’t have to do a single thing to their bodies either to be lesbian/gay or to be happy to be lesbian/gay. Not one thing. People who claim to be the opposite sex often want to do very drastic things to their bodies, and many of them are very young. That’s a huge difference right there.

And then, sexual orientation just is. There’s no element of fairy tale or woo – it’s just that some people fancy the other sex and others fancy the same sex. Who fancies whom and why is maybe a little bit complicated, but it’s not outright Let’s Pretend.

At least some of the adults at Amnesty UK must know all this, yet they carefully hide it in this stupid obfuscating statement. It’s appalling.

So there’s a butterfly sanctuary in Texas, just north of the border with Mexico. Trump wanted to build a new section of border wall through the butterfly sanctuary, even though the sanctuary is not in Mexico or even touching Mexico. The butterfly sanctuary does not endorse this plan. Therefore, the lunatics hate the butterfly sanctuary and have been trying to break it.

A Congressional candidate and someone she called a “Secret Service agent” showed up at the sanctuary and demanded entry “so that they could go see ‘illegals crossing on rafts’.”

“Immediately, we knew what that was about,” [Marianne] Wright told The Daily Beast on Thursday. “It was an echo and reiteration of the lies Steve Bannon’s ‘We Build The Wall’ campaign published and promoted against us for years.”

Wright is the executive director of the National Butterfly Center, a private nature preserve in Texas’s Rio Grande Valley. The center is a sanctuary for hundreds of butterfly species—and a frequent target for conspiracy theorists after Wright and her colleagues opposed the Trump administration’s plans to build a border wall through the middle of the property.

…

Although the National Butterfly Center is located in Texas, Donald Trump’s proposed wall would run two miles north of the U.S.-Mexico border, bisecting the protected land. In 2019, the center filed a restraining order against the construction project. That court filing made the center a fixation of the far right.

One Trumpist group, the Bannon-backed “We Build the Wall” campaign, targeted the center with conspiracy theories. Brian Kolfage, a leader of the group, repeatedly tweeted that the National Butterfly Center was harboring an illegal sex trade and dead bodies.

Sounds like that DC pizza parlor that kept – what was it? child prostitutes? – in its basement, at the behest of Hillary Clinton.

By late 2019, conspiracy theorists were circulating memes falsely accusing the National Butterfly Center of being a front for sex traffickers. Wright and colleagues faced in-person threats from members of militia groups like the Oath Keepers and the Three Percenters, as well as threatening phone calls and emails from a man who was revealed to be a Texas police officer.

It’s impressive the way they kill multiple birds with one stone. Butterfly sanctuaries have nothing to do with border policy or immigration or MAGA or any of it but hey, there’s one sitting there, super close to the border, so might as well try to stamp out interest in nature, protection of wildlife, educational projects, and all that hippy shit, yeah?

Updating to add: I think I got it wrong about the butterfly center not touching Mexico. The article doesn’t say that, I find on reading more carefully, and on Google maps it looks as if it’s bordered by the river, so in a sense it does touch Mexico. I say “looks as if” because the map doesn’t have a border mark other than the river.

While there I took a look via streetview. Recommended.

Yes, this is definitely what billionaires should be doing to hasten global warming.

A historic bridge in Rotterdam, Netherlands, is to be dismantled so that Jeff Bezos’ superyacht can pass through.

Sure, that’s fine. Waste resources on breaking a bridge so that an egomaniac can move his egomaniacal boat from A to B.

The Koningshaven Bridge, nicknamed “De Hef” by locals, has been a landmark in Rotterdam since 1878.

Then it’s high time some piggy Yank came along and broke it. Good job Bezos.

Now, it is to be dismantled to let the Amazon founder’s 127-meter (417-foot) long luxury sailing yacht – the Y721 – to reach the ocean. The yacht will be the largest vessel of its kind in the world, and will be unable to make it under De Hef when it is completed by the ship-making firm Oceanco. Despite promises that the bridge would not be dismantled again following renovations in 2014-2017, the middle section of the bridge will be temporarily removed to let the billionaire’s boat out.

Which is more important, not breaking a perfectly good bridge or giving a piggy demanding billionaire exactly what he wants?

“It’s the only route to the sea,” a spokesperson for the mayor’s office explained to AFP, adding that building the yacht created jobs, and that the bridge would once again be restored once the job was complete.

If the goal is creating jobs why not just hire a bunch of people to take the bridge apart altogether and then rebuild it? And then do it again? No need for Bezos to get involved at all.

Man tells Martina Navratilova she knows nothing about it.

What does India Willoughby – a man – know about being a woman? Nothing, so what’s he doing telling Martina Navratilova she doesn’t have the relevant knowledge about the way men like India Willoughby try to silence women?

Willoughby has ZERO idea what it’s like to be a woman in the UK (or anywhere else) yet he tries to silence women who talk about it. Sauce for the gander mate.

Updating to add Willoughby’s new level:

The full image doesn’t show; the first word of the headline is “Martina.”

And another thing, kids: you get to win in ALL the categories!

Schneider wins in the First Woman category AND the Trans category. Win win win win win! You might think that doesn’t make sense, that it should be one or the other, but NO – that kind of logic applies only to cis people. Check your thinking.

Huh.

Old Square Chambers is delighted to announce that Robin White has been shortlisted for an award at the Women, Influence & Power in Law UK Awards 2022, which will take place on Wednesday 18th May 2022 at the Hilton Bankside.

He’s a man.

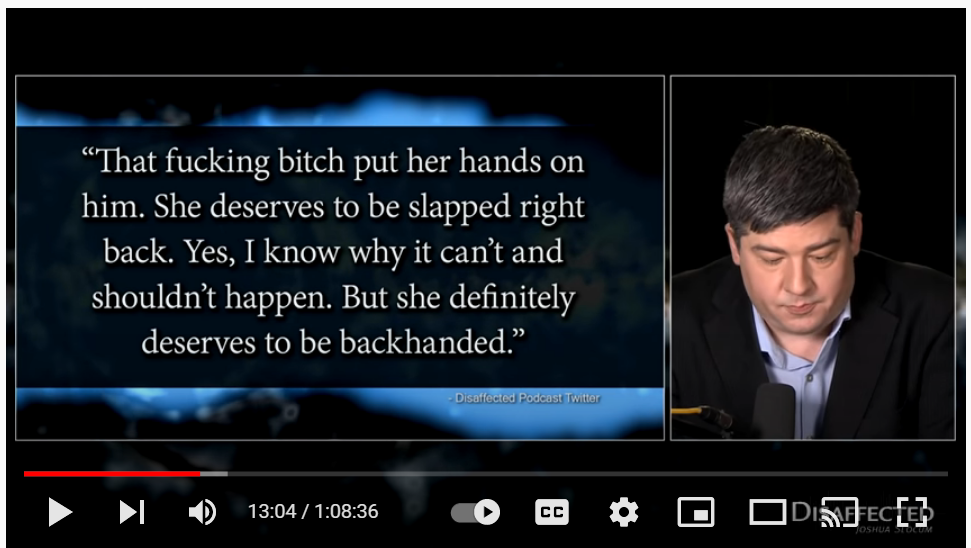

Ah yes. “Shut up about your stupid ‘violence against women’ problems, focus on trans women. Exclusively.”

It’s a detail but…oh my god the childish mindless destructive stupidity.

Some Trump White House documents preserved by the National Archives were ripped up by the former president and had to be taped back together by government officials, the records agency said Tuesday.

“Some of the Trump presidential records received by the National Archives and Records Administration included paper records that had been torn up by former President Trump,” the agency said in a statement to NBC News. “As has been reported in the press since 2018, White House records management officials during the Trump administration recovered and taped together some of the torn-up records,” a reference to reports that Trump habitually ripped up documents and threw them away after reading them.

It’s the “habitually” that drives me crazy. Break the habit then! Act like an adult! Act like an adult with a serious adult job that has an impact on billions of people! Find out what the rules are and then follow them. The rule is that such documents are to be preserved, period, no exceptions. He’s not allowed to “rip them up” as if they were yesterday’s grocery list.

The President Records Act requires that all presidential records be turned over to the National Archives at the end of their administrations, the agency’s statement noted.

Politico reported in 2018 that White House officials had to use clear Scotch tape to reconstruct large piles of shredded paper from former President Donald Trump as if it were a “jigsaw puzzle.”

He’s that stupid and heedless. A building should fall on him.

Pronoun badges have been introduced at the British Library on the advice of Stonewall, despite fears the move could appear “too woke”

Never mind “too woke”; that’s too sophisticated for this childish nonsense. Pronouns are how we refer to other people so as to avoid repeating their names every time we mention them. That’s it; end of story. They’re not little pills to boost people’s feelings of Validation or Chosenness. The whole idea of personalized pronouns is idiotic, and bragging about them is even more so. That the British Library has fallen for the idea is embarrassing.

Labels displaying “he/him”, “she/her” or “they/them” have been rolled out for staff, with internal documents stating that making assumptions about gender can send a “harmful” message “even if correct”.

No it can’t. Recognizing who is female and who is male doesn’t send any message, any more than recognizing who is human and who is equine does. It’s not a message, it’s just knowing where we are in the world.

The assessment for the rollout of the voluntary badges stated that it could be perceived as “political” and that the £1,300 cost of the scheme could lead people to question “why is the BL (British Library) spending money on this in times of financial difficulties?”

More to the point, the BL might as well flush that £1,300 down the toilet. Why waste £1,300 on annoying bullshit? And for that matter, why does it cost £1,300? Isn’t all but about £20 of that just profit for Stonewall? They don’t make the badges out of gold leaf, I’m betting.

An internal email laying out the scheme states that the “aim of these badges is to encourage discussion and understanding of gender identity and the range of identities that people have”.

But that’s a bad, stupid, wrong discussion, so it’s bad to encourage it.

Oh here it is, the Telegraph does explain where all that money goes.

The library’s badges were introduced in September, with provisional budgets estimating a cost of £676 for the 400 badges themselves, £450 in “trans awareness training”, and £250 for the services of the same transgender awareness consultant who recommended the scheme. This may not have been the final budget.

“The services.” What services? It’s such a Ponzi scheme. Pay us to tell you what to pay us to tell you; profit!

An internal message titled “Introducing Pronoun Badges” outlined the purpose of the scheme last year, stating: “By wearing a pronoun badge, even if your pronouns are rarely if ever used incorrectly, you are sending a message to colleagues, visitors and readers that you recognise the validity of pronouns other than what is immediately obvious.”

But again, there is no such thing, so it’s bad to send a message that you “recognise” this stupid thing that doesn’t exist.

It added that part of the aim was to “continue to make a more inclusive environment for trans and non-binary collgeaues and visitors at the British Library”.

You’d think they were the only people on earth. No. This is as inclusive as we’re going to get, so take your expensive pronouns away and don’t come back.

The trajectory of [Bandy] Lee’s life had indeed taken a strange turn of late. A widely respected scholar who has authored over 100 peer-reviewed articles and either written or edited a dozen academic books on violence, Lee was an assistant clinical professor in the law and psychiatry department at Yale for 17 years until the summer of 2020, when Yale declined to renew her contract. The precipitating offense? Tweeting about the retired Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz.

Academics aren’t allowed to tweet about Alan Dershowitz?

Lee claims it was all Dershowitz’s doing: “Dershowitz’s pressure seems to be the reason why everything changed.” But Lee had long been one of her department’s most controversial members, thanks to her outspoken, boundary-pushing commentary about Donald Trump. Still, while her department chair, John Krystal, had never liked the public attention her comments attracted, he had tolerated them as long as she made it clear that she was not speaking on behalf of the department.

…

Lee paid little attention to domestic politics until 2016. “The morning after Trump was elected president, I decided to do something because I was convinced that his administration was likely to increase violence,” she said. The following spring, Lee organized a conference at Yale titled “Does Professional Responsibility Include a Duty to Warn?” on the subject of Trump’s mental state and the ethics of psychiatrists diagnosing him from afar. She respected the Goldwater Rule — the ethical guideline designed to prevent psychiatrists from rendering a professional opinion of a public figure without first receiving permission and conducting an examination — but she also worried about “the risk of remaining silent.”

The conference led to a 2017 book, The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump, which argued that Trump’s lack of “mental fitness” made him a threat to the nation. As Lee and Harvard Medical School psychiatrist Judith Herman put it in their introduction: “Delusional levels of grandiosity, impulsivity, and the compulsions of mental impairment, when combined with an authoritarian cult of personality and a contempt for the rule of law, are a toxic mix.” With contributions from 27 mental-health experts, the book, which sold more than 100,000 copies, claims that Trump likely suffers from a grave personality disorder such as malignant narcissism.

Maybe he doesn’t though. He obviously is a malignant narcissist, but maybe that’s not the same as suffering from the grave personality disorder malignant narcissism.

On January 2, 2020, Lee posted a few tweets about a comment that Dershowitz had made in response to an accusation by one of Jeffrey Epstein’s victims that Epstein had forced her to have sex with Dershowitz. “I have a perfect, perfect sex life,” he had told Fox News.

Lee said some things about that claim, Dershowitz was enraged, and Lee’s contract was not renewed.

Yale’s argument in the case is that, though all its professors have the freedom to express their views, the university also has the academic freedom to decide which professors to retain. Several professors I spoke to seemed skeptical of the school’s claim.

“A university does have the right to fire someone whose work is substandard,” Laurence Tribe, a Harvard Law professor and constitutional scholar, told me. “But it is hypocritical for Yale to punish Lee simply for criticizing a couple of powerful people — namely, Trump and Dershowitz. That endangers the whole academic enterprise. Lee has a strong case.”

Lee’s lawyer, Robin Kallor, concedes that private universities, unlike public universities, are not necessarily bound by the First Amendment. “But Lee was protected by a Connecticut statute that prohibits retaliation through discipline or discharge for exercising speech rights protected by the U.S. Constitution and Connecticut Constitution,” shesaid.

Richard Painter of the University of Minnesota, who served as George W. Bush’s ethics counsel, says that non-tenured faculty like Lee are employees at will and can be terminated at any time under contract law, but that “universities do make exceptions and academic freedom is one of those exceptions. And Yale took a very strong stand on academic freedom in its Woodward report, which remains in its faculty handbook.”

It’s complicated, in interesting ways.

All are welcome.

Ok not all. Some. Some are welcome. Not you. You’re not welcome.

It actually does say on its homepage: ALL WELCOME.

Category Is Books is an independent LGBTQIA+ bookshop in the southside of Glasgow.

We hope the bookshop is a space to learn about, be inspired by and share in our love of queer books, history, art, activism, writing and storytelling.

Terms and conditions apply.

Queer love, power and solidarity to you all!

34 Allison Street, Glasgow, G42 8NN

ALL WELCOME

Let not thy left hand know what thy right hand doeth.

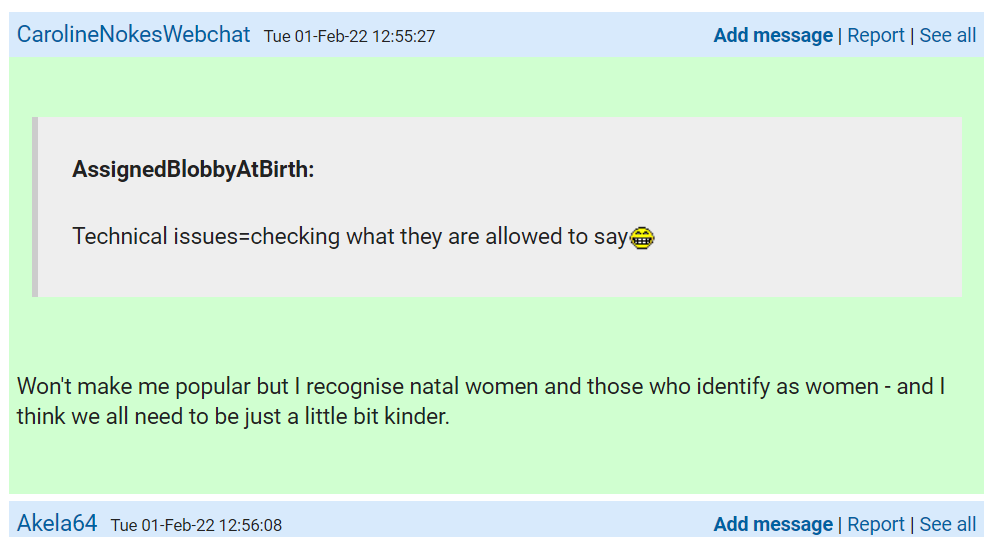

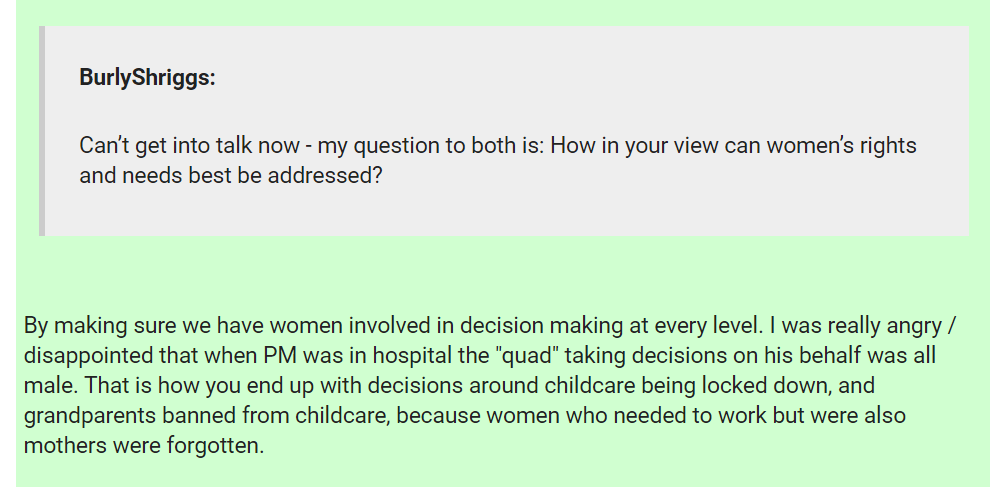

Ah yes be kind. Get more women involved in politics, including men of course, and above all be kind.

Ok but suppose we all do be just a little bit kinder, i.e. define women as including men who say they are women – what then?

Then getting more women involved in politics could be done by getting more men (of the self-declaring as women variety) involved in politics – so what’s the point? Why not just settle for people involved in politics and let it go at that? Why try to keep track of ways women are excluded if it turns out men can be counted as women?

Also Caroline Nokes:

What if the quad making decisions were all trans women? Wouldn’t you still end up with decisions around childcare being locked down, and grandparents banned from childcare, because women who needed to work but were also mothers were forgotten? Wouldn’t men who call themselves women forget the needs of women with children just as much as men who don’t call themselves women do?

Does Caroline Nokes actually think that men who call themselves women are more aware of the needs and responsibilities of women? If so she couldn’t be more wrong. Those men are aware of their own needs, or rather their wishes. The needs and wishes of women are just an obstacle to be brushed aside for men like that.

Mumsnet is doing a live conversation with MPs Stella Creasey and Caroline Nokes today. So what do we get?

IdealisticCynic

To both: I think it will impossible to understand the context and proper content of any answers you may provide on women and mothers in politics without an answer to a question posed by others already:

How do you, personally, define a woman?

How odd that we’re in a place where anyone has a “personal” definition of women. Such definitions have to be universal to be any use.

Hi – Caroline here – and happy to be able to take part today.

I think it is really important to focus on this being a chat about how we get more women involved in public life. I want that to be all women, natal women, transwomen, and those who self-identify and do not yet (or perhaps ever) have a GRC.

So there we go, the whole discussion is pointless. Nokes thinks some men are women, so anything she goes on to say about getting more women involved in political life is just plain meaningless. She would consider it “getting more women involved in political life” if a whole lot of men who call themselves women got involved in political life.

What an absolute farce.

Screenshot:

It’s maybe not ideal if the police have contempt for broad swathes of society, like for instance women and Other races. That’s because they’re the police. They have police power over us, so if they hate many of us going in, they might abuse that power they have.

Metropolitan Police officers joked about raping women, beating up their partners and killing black children, a damning report by the police watchdog has found.

…

Nine linked investigations were launched by the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) in 2018 following reports that a police officer had sex with a drunk person at a police station.

The Telegraph gives examples of the “jokes,” including one about grinding up African children to make dog food.

When challenged many of the officers dismissed the exchanges as “laddish banter ” but the IOPC said it was deeply worrying.

What does “laddish” mean? Misogynist, basically. You don’t want cops swapping misogynist jokes, even if you label them “laddish banter” as if that were somehow nicer.

The report comes as the Met is still reeling from the fallout following the kidnap, rape and murder of Sarah Everard by serving officer, Wayne Couzens.

Is it possible that Wayne Couzens isn’t misogynist at all, but simply wanted to fuck a woman that night and decided to skip his wife and instead grab a stranger off the street and then kill her after the fuck? It doesn’t really add up, does it. Sex with his wife would have been a whole lot safer and easier, not to mention harmless to all other women. Grabbing a woman in Clapham, driving her all the way to Kent, and killing and hiding her after raping her is hours and hours of work. Years and years of training in hatred and contempt are needed to motivate that level of effort.

“Protesters” attack people feeding the homeless in Ottawa.

Ottawa’s Shepherds of Good Hope has received an outpouring of support and donations after its staff were harassed and a client was assaulted by “Freedom Convoy” protesters on the weekend.

Freedom freedom freedom: freedom to harass and assault people.

On Saturday, a group of protesters associated with the convoy of truckers and supporters railing against COVID-19 health measures in downtown Ottawa harassed staff and demanded food from its soup kitchen in an altercation that lasted for hours. Shelter officials described their behaviour as “mob-like”.

It’s almost as if libertarianism and assholism go together.

Earlier, a man who lives in the shelter was assaulted outdoors by protesters who then hurled racial slurs at a security guard who went to assist him, the shelter’s president and CEO said Sunday.

Deirdre Freiheit said the situation was upsetting for everyone. Staff members, who were being harassed, initially served meals to some of the protesters in order to de-escalate the situation, she said.

“Freiheit” is German for “freedom.” Ironic, ain’t it.

“It was a very difficult day for them. The disruptions were many. They are working hard, they are tired and we are short-staffed. When people are taking away their ability to provide services to many of the most vulnerable people in the city, it is very discouraging.”

No no no it’s an exercise of Freedom.

For much of the day Saturday, access to Shepherds, at the corner of Murray Street and King Edward Avenue, was blocked by unattended protest trucks that were left running. Freiheit said that meant ambulances were unable to get in and staff had a more difficult time reaching people in the community who might be overdosing or in need of help.

And why were the trucks left running? Just to make everything that much more shitty? To show off their freedom to make global warming that little bit worse for the sheer hell of it?

He’s the mayor.

H/t Roj Blake

The Mayor of Bangor is distraught.

Ah um er – by “bathroom they are entitled to” he must mean the women’s – so his partner and partner’s squeeze were squeezed into a single cubicle to…

So anyway they got thrown out, to the relief of a lot of women with bursting bladders, I should think.