Hipster captioning.

The full caption:

Hipster captioning.

The full caption:

Suddenly the BBC is being a good deal more blunt:

A trans woman who groomed and had sex with a 14-year-old girl, making her pregnant, has been jailed.

The defendant – named by police as “David Orton, also known as Danielle Rose Gemini” – was found guilty of penetrative sexual activity with a child following a trial.

…

The offender, whose name was recorded as Danielle-Rose Gemini by Leicester Crown Court, was jailed for nine-and-a-half years.

Leicestershire Police – who said the 25-year-old identified as a woman at the time of the offences – were not able to give a current gender identity.

That “who said the 25-year-old identified as a woman” is two layers of skepticism right there in the open. There’s not a word of sympathy or tender concern for him anywhere in the article.

Interesting.

End violence against women…

…unless of course that might inconvenience men who call themselves women.

A charity event to push for an end to male violence against women and girls has banned discussion about single sex spaces.

Push for an end to male violence! But don’t push hard – in fact push as gently as you possibly can.

Nicola Sturgeon, the first minister, is scheduled to give the main speech to the 30th anniversary gathering by Zero Tolerance in Edinburgh today. The charity‘s core belief is that male violence should not be tolerated.

Unless the male “identifies as” a woman. Then the violence is quite all right.

A note sent to attendees said it wanted “to create a safe and supported environment for our guests and ask you to support us in this aim by refraining from discussions of the definition of a woman, and single sex spaces, in relation to the gender recognition act”.

It added: “As feminists we have strong opinions on these subjects, but this is not the place for that conversation.”

Of course it is. It’s exactly the place for that conversation. How the hell can anyone campaign to end violence against women if nobody knows what a woman is? How can anyone campaign to end violence against women if no one is allowed to talk about women? How can anyone campaign to end violence against women if men who claim to be women have to be “included” in everything women do? How can anyone campaign to end violence against women if we’re all too anxious and “polite” to say men are not women?

Sturgeon is giving a speech at the event.

The decision might have been made to “save the blushes of the first minister”, suggested Marion Calder, director of For Women Scotland.

Here’s an idea: don’t bother to save Sturgeon’s blushes. She should be blushing. More to the point, she should not be favoring men who pretend to be women rather than women.

Won’t someone please have some sympathy for the poor beleaguered fragile trans laydee who makes racist taunts?

He’s deleted the tweet but there are many many screengrabs.

The enlightened sympathize with India but also remember to be intersectional.

But don’t ever ever ever be better than calling a woman a cunt. That’s absolutely fine, in fact it’s obligatory.

And how are we defining equality exactly?

What does it mean to “police” who is a woman? It doesn’t seem like something anyone can police. Either you are or you aren’t. It’s commonplace to police things like who is a citizen, who is a lawyer, who is a doctor, who is an Olympic medalist – that is, there are criteria for all those things, which can be lied about or faked. You don’t want a pretend dentist messing with your teeth.

But who is a woman and who is a man aren’t like that. There are criteria in a sense, but they’re built in. It’s almost always obvious, and it used to be taken for granted. Now suddenly it’s a matter of “policing,” and women are ordered to accept anyone who claims to be a woman as a sister, especially when the person doing the claiming is a man.

What does that have to do with equality?

Still working on the government by force thing.

And who should do the installing? The military?

Much of Lake’s Trump-backed campaign was centered around bolstering unfounded claims of electoral fraud in the 2020 election, and the former TV anchor has lived up to her commitment to only accept election results if she won.

Lake, who lost her bid for governor to Democrat Katie Hobbs, has refused to acknowledge the election results, instead filing a lawsuit requesting public records from Maricopa County that would detail which voters experienced issues casting their ballots, and information regarding errors in ballot counting.

“We know we won this election,” Lake said in a weekend interview with far-right streaming service Real America’s Voice. “We are going to do everything in our power to make sure that every single Arizonans vote that was disenfranchised is counted.”

Trump “knew” he “won” too.

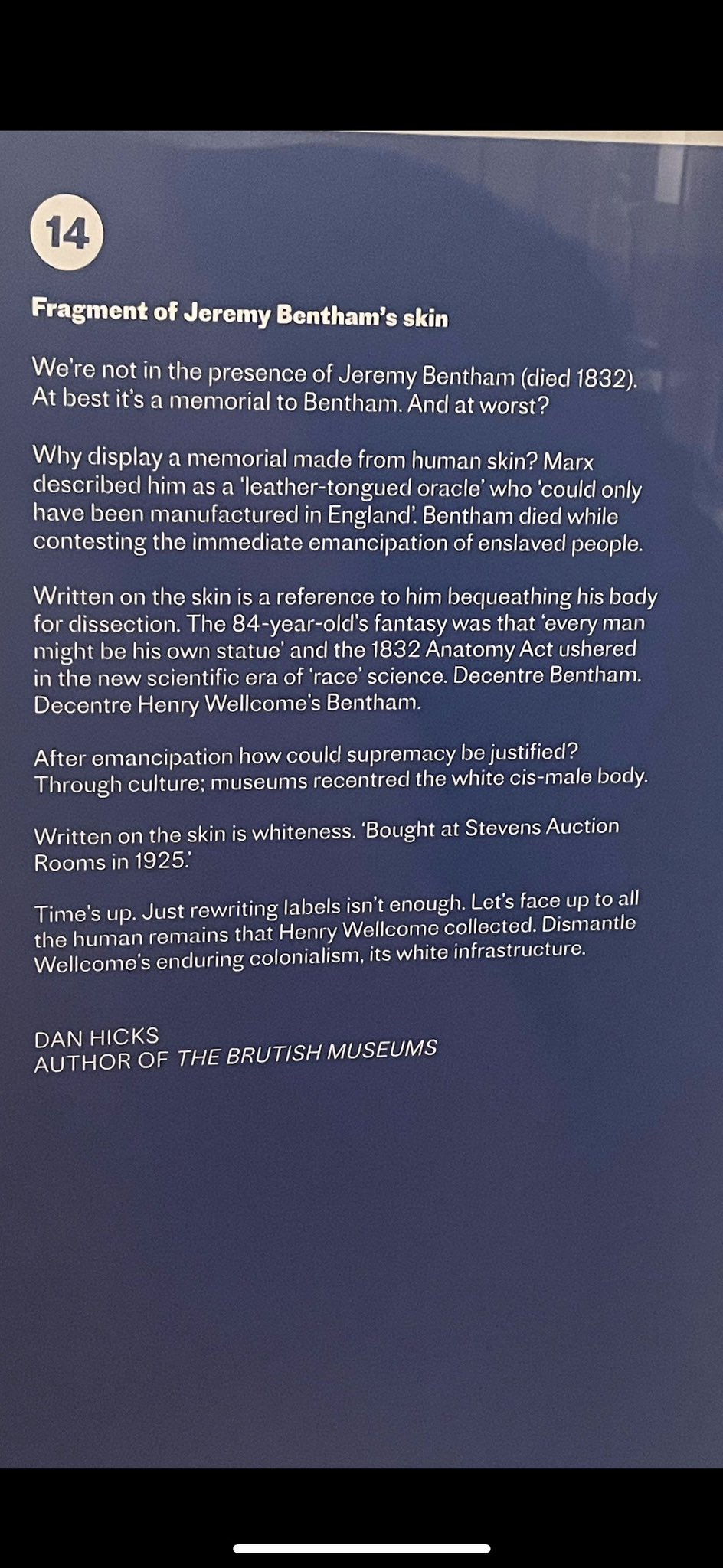

A museum in London is closing one of its main exhibitions following concerns over “racist, sexist and ableist theories and language”.

The Wellcome Collection says the Medicine Man display is ending after a 15-year run. Founder Henry Wellcome, who died in 1936, collected more than a million objects to give an insight into global health and medicine. The museum has marked the closure as a “significant turning point”.

Controversial objects include a 1916 painting titled “A Medical Missionary Attending to a Sick African” which depicts an African person kneeling in front of a white missionary.

It’s pretty obvious why that would be controversial. I wonder if they could just mark it historical with a note that views and attitudes have changed.

The museum said in a statement on Twitter: “We can’t change our past. But we can work towards a future where we give voice to the narratives and lived experiences of those who have been silenced, erased and ignored.

“We tried to do this with some of the pieces in Medicine Man using artist interventions. But the display still perpetuates a version of medical history that is based on racist, sexist and ableist theories and language.”

At least they didn’t say “transphobic theories and language.”

I don’t know. I’m seeing a lot of skepticism, but maybe the Wellcome would benefit from some updating. Then again maybe the people doing the updating will be a shade too righteous or smug or both to do a good job of it.

Zoe Williams at the Guardian tries to rebuke Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie for not having approved opinions:

Five years ago, the writer said in an interview: “When people talk about, ‘Are trans women women?’ my feeling is trans women are trans women.” She has written extensively about the fire she came under after that.

…

This is the driving logic of her fear for free speech: that she can’t say biological sex is inalienable without sparking a storm. “So somebody who looks like my brother – he says, ‘I’m a woman’, and walks into the women’s bathroom, and a woman goes, ‘You’re not supposed to be here’, and she’s transphobic?” We break briefly so I can look at a photo of her brother, who is smiling, tall, bearded and handsome. He’s actually on this trip with her; she has five siblings in all, two sisters, three brothers, all very close. I suggest that he would look different if he were living as a woman.

Oh well that’s all right then. The beard is gone and he’s wearing lipstick so it’s fine for him to barge into the women’s toilets.

“But that’s the thing,” she says. “You can look however you want now and say you’re a woman.” And, she adds, anyone who might take issue with this is “outdated” and needs “to have the young people educate [them]”. I suspect she’s taking an argument – that trans people don’t want to be policed for how they dress and what stage of transition they’re at – and reducing it to the absurd.

No, she’s not reducing it to the absurd; it is absurd. It’s already absurd, without any help from Adichie. It’s absurd that people think they can change sex, and that men are women if they say they are. The whole ideology is completely absurd.

I suspect she’s taking an argument – that trans people don’t want to be policed for how they dress and what stage of transition they’re at – and reducing it to the absurd. So I tack another way: “Imagine your brother did want to live as a woman. You would support his endeavour with love, right? You’d probably think treating him with dignity and respect was more important than where he went to the toilet?”

“But why is that?” she asks. “Why can’t they be equal parts of the conversation?”

“Maybe because dignity is more important?”

Whose dignity??? Whose motherfucking dignity? Why is it always the “dignity” of men who claim to be women that’s under anxious protection in these conversations, while the “dignity” of women is summarily thrown out the window? Why is Zoe Williams so eager to see women forced to share toilets with men?

“Not if you consider women’s views to be valid. This is what baffles me. Are there no such things as objective truth and facts?”

I’m not having that. “You couldn’t objectively say, ‘All women are threatened by trans women.’ I’m also a woman. That doesn’t reflect my experience.”

Oh, she’s not having it. Isn’t she the feisty one. But the objective truth and facts aspect is about the objective truth and fact that men are not women. That’s it. Men are not women, therefore the two facts that men are stronger than women and that some men will assault or molest women if given the opportunity are relevant to the whole conversation about women’s right to say no to men.

“No, of course not. And it would not reflect the experience of many people. I think that’s different from saying, ‘Women’s rights are threatened by trans rights.’”

I think the opposite is true – and since I’m in the oppressed category whose rights she’s wanting to protect, I think we have to file the matter under, at best, not-yet-settled. Then we drop it since, realistically, we could fight about this all day and she has a flight to catch.

Williams thinks the opposite is true – so she thinks trans rights are threatened by women’s rights? That’s certainly an interesting take. It’s probably not what she meant, she probably meant women’s rights are not threatened by trans rights, but that’s almost as stupid and abject. All these years, and I still find people like her astounding.

Originally a comment by Your Name’s not Bruce? on What Jesus had.

Hang on. “Evidence” based on “Renaissance and Medieval paintings of the crucifixion” is from images created centuries after the event being depicted, interpreted through the lens of gender-theoretical wishful thinking invented centuries later still. That is a helluva long chain of evidence, but then if you’re a gender studies “scholar” you can just make shit up as you go along, without the tedious burden of proof. Assertion is sufficient; it’s self ID for “evidence.”

But maybe there’s more to it than we’re giving credit for; perhaps one of these artists came into posession of a contemporaneous, eyewitness sketch made on Golgotha? We already know that depictions of The Last Supper are notoriously fraught with controversy. It should come as no surprise that The Crucifixion should engender similar conflicts. We must keep an open mind. I am open to persuasion.

We’d find the most tenuous, shallowest, most superficial similarities and connections, ultimately generating readings that directly opposed the straightforward interpretation of the text. Or turned everything into sex, because we were teenagers.

Yes, I could see how an over-Butlered man might get excited about the idea that the thrust of a spear could open a neo-vagina in the body of a brave and stunning, marginalized, spiritual being, who was born into, and trapped within, a vessel of human flesh, destined and condemned to be invalidated and mis-gendered, fated to submit to the scorn, hatred, and genital inspections of the world. It almost writes itself. Christ in the image of Trans. Now that’s centering! Too bad they didn’t stick the landing, though. For this hypothesis to be truly persuasive, along with the abdominal “wound-vaginas,” the depictions of Christ on the Cross should have featured Their Crown of Thorns sitting atop blue hair.

I’ve always found it quaint how some people, astronomers, theologians, or civilians, go to the trouble of coming up with an actual astronomical phenomenon upon which the Star of Bethlehem might have been based, a planetary conjunction or comet being favourites. But in order to hang the tale (which is in Matthew only) on one of these bright objects that actually do appear in the night sky, they have to throw out other aspects of the story, like how it led the magi, and then stood still over the place where Jesus was. There are no astronomical phenomena that behave in this manner. You can either have your “scientific” validation, or you can have your miracle. You can’t have both. One vitiates the other. (Never mind the magi were supposed to be “from the East”, yet they had seen the star “in the East”, which would suggest that magi from Mesopotamia, say, should have been heading towards India, rather than Palestine. It’s postmodern geography. Whatever.) This “Jesus was trans” idea sounds like more of the same, without the sort of tenuous constraints of the “astronomy” appealed to in the Star of Bethlehem story. Once you’ve cut the surly bonds of reality, you can let your ravings imagination soar freely.

Speaking of rights, and “trans rights,” and the refusal ever to define exactly what “trans rights” are – a gaggle of “trans activists” have scored another self-defeating triumph.

“Trans rights are human rights” they chant idiotically, as if anyone were trying to take human rights away from trans people. Funny how they chant it while impeding women’s rights.

Intimidation tactics much?

Trans rows are splitting the Greens, the Times says.

…the Green Party has now been accused of neglecting its core aims after becoming so embroiled in arguments about gender that three prominent members are suing over the issue.

The trio allege they were disciplined, abused and even assaulted over their views on trans rights.

Wait. That’s not the right way to frame it. That makes it sound as if dissenters want to remove actual rights from trans people. We don’t. The point is that there are endless wild claims about putative trans rights that aren’t rights at all, for anyone. I don’t have any right to force people to agree that I’m a tree or a tank or a jar of marmalade. Trans people should have all the rights the rest of us do.

The former deputy leader Shahrar Ali, the former Green Party Women co-chairwoman Emma Bateman and the former executive committee member Dawn Furness are taking legal action against the party, alleging that their views led to smears and suspensions.

Ali, Bateman and Furness have begun separate legal claims amid allegations that the party typically associated with peaceful protest and social justice has become a “deeply hostile environment” for anybody who “dares to question” the rights of transgender people. The Green Party’s official stance is that “trans women are women” and “trans men are men”.

Again, those are two different things. A definition is not the same thing as a right. We disagree with the Green Party’s official stance that trans women are women, but that’s a factual disagreement, not a disagreement over rights. It’s only if you decide that there’s a “right” to force people to agree with absurd new counterfactual definitions that the dispute becomes about rights. Let’s not assume that, ok?

While lauded as a policy of acceptance, it has been questioned by others who claim that “as a party of science” on the climate change issue, it lacks credibility if it “can’t define between a man and a woman”.

More muddle. Acceptance is one thing, definition is another. It’s “distinguish between,” not “define between.” The meaning I suppose is that insisting that men can be women equals acceptance of trans women, but it’s important to do all the steps. The discourse on this subject is chaotic enough already without making it worse.

Last week Alison Teal, 56, who had been selected to stand as a Green Party MP at the next election, was suspended by party headquarters after she posted on social media calling for a “discussion” and linking supporting trans women to the “loss of women’s rights”.

…

Teal said she was “shocked” by her no-fault suspension, which she feels is “becoming a distraction”. She said: “For the Green Party, with the climate and biodiversity crisis, it doesn’t make sense for us to be stuck on the identity politics issue.”

But narcissism doesn’t care about your stinkin’ climate crisis: this is about authentic selves.

Ali, 53, the Green Party’s deputy leader between 2014 and 2016, based in London, was sacked as spokesman on policing and domestic issues in February after questioning its stance on trans rights.

Rights? I doubt that. I think he questions its stance on definitions, demands, punishments. If the writer (Glen Keogh) could manage to say “definitions of rights” or the like, I wouldn’t object, but just referring to “trans rights” and saying critics oppose them is highly misleading.

Bateman, who joined the Greens in 2009, says she was “aggressively shut down” when she tried to question the party’s stance on trans rights. She has been suspended twice.

Sigh. Not trans rights; putative trans rights.

“Gender ideology is wrecking the party,” Bateman said. “The reason I have taken this legal action is we are losing all credibility. We are the party of science, where our base policies are on climate change. If we can’t answer ‘what is a woman?’ we lose all credibility.”

See? She didn’t say “If we can’t take away trans rights”; she said “If we can’t answer ‘what is a woman?’” That’s a different thing.

Last year Sian Berry, a vocal supporter of trans rights, quit as leader, citing conflict over the transgender debate. She said she could “no longer make the claim that the party speaks unequivocally, with one voice, on this issue.”

Sigh.

Maybe it’s the Green Party statement that got the reporter off on the wrong track.

A spokesman for the Green Party said: “We do not comment on individual disciplinary cases.

“The Green Party is clear that trans rights are human rights.”

But what are trans rights? Of course the GP doesn’t say, just as Finn Mackay didn’t say.

So would I.

On the one hand, anyone with a cervix. On the other hand, anyone with a prostate men aged 50 and older.

On the one hand, anyone with a cervix. On the other hand, real people who matter.

Trendy god-botherer says Jesus was maybe trans.

Jesus could have been transgender, according to a University of Cambridge dean.

Dr Michael Banner, the dean of Trinity College, said such a view was “legitimate” after a row over a sermon by a Cambridge research student that claimed Christ had a “trans body”, The Telegraph can disclose.

The “truly shocking” address at last Sunday’s evensong at Trinity College chapel, saw Joshua Heath, a junior research fellow, display Renaissance and Medieval paintings of the crucifixion that depicted a side wound that the guest preacher likened to a vagina.

Time out. I have to spend a few minutes laughing here.

Right. Some medieval and Renaissance paintings of the crucifixion show a stab wound because there’s a bit in John where a soldier poked him with a spear. Now what is a stab wound from a spear going to look like? It’s going to be a slit, right? Not a big gaping hole and not a little hole like a bullet wound, but more of a slit. Heeeeeeey insight: “slit” is slang for vagina. Boom, there’s your vadge in Jesus’s side. Is that profound or what?

Heath, whose PhD was supervised by the former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams, also told worshippers that in the Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg, from the 14th century, this side wound was isolated and “takes on a decidedly vaginal appearance”.

Maybe because the artist was having a laugh.

Heath also drew on non-erotic depictions of Christ’s penis in historical art, which “urge a welcoming rather than hostile response towards the raised voices of trans people”.

Naaaaaaaaaaah. I’ve had enough of those raised voices to last several lifetimes.

“In Christ’s simultaneously masculine and feminine body in these works, if the body of Christ as these works suggest the body of all bodies, then his body is also the trans body,” the sermon concluded.

That’s just silly. Where’s the makeup? Where are the crippling shoes, the Prada briefcases, the botoxed lips?

There was a complaint letter.

Dr Banner’s response to the complaint, seen by The Telegraph, defended how the sermon “suggested that we might think about these images of Christ’s male/female body as providing us with ways of thinking about issues around transgender questions today”.

Well, one, what if we don’t fucking want to think about “issues around transgender questions today”? What if we’ve heard way way way more than enough about those “issues” and think we should talk about real issues instead? What if we think there are vastly more important issues, like the death of the planet, wars on women in Iran and Afghanistan and the list is endless, the grotesque gap between the poor and the rich in the US, wars, racism, famines, pandemics? What if we think boring little drones whining about their idenninies just don’t matter that much in comparison?

Finn Mackay continues not to answer the many people who have asked “What rights are you talking about when you say ‘What do we want: trans rights, when do we want them: NOW.'”

It’s odd. It seems like a perfectly good opportunity to say what trans rights, so as to further public understanding of the trans cause.

Maybe Mackay understands that the purported rights aren’t actually rights? That no one has a “right” to force people to agree that people are a thing they visibly obviously unmistakably are not? That men don’t have a “right” to take over women’s sports? That men who say they are trans don’t matter more than women? Maybe Mackay realizes the shouting and threatening and bullying are not working as well as they once did? That more and more people are realizing how absurd at best and destructive at worst the demands are?

Or maybe Mackay is just lazy, I don’t know.

More on the friendly Florida teet-deleter:

Ah yes, that’s so funny, that face expressing confusion/disgust at the very idea that it’s not ethical to market mutilations, let alone performing them. Yes, doc, there are ethical reasons for not rushing to slice off teenagers’ breasts or penises on demand.

It was probably humans who killed off the megafauna.

For a long time, these extinctions were thought to be linked to natural changes in the environment – until 1966, when palaeontologist Paul S Martin put forward his controversial “overkill hypothesis” that humans were responsible for the extinctions of megafauna, destroying the romantic vision of early humans living in harmony with nature.

Well, it was harmony from the early humans’ point of view.

Prof Mark Maslin, from University College London (UCL), suggests that the unsustainable hunting of megafauna may have been one of the driving forces that led humans to domesticate plants and animals. People started farming in at least 14 different places, independently of each other, from about 10,500 years ago. “Weirdly enough, I think the first biodiversity crisis was at the end of the last ice age, when early humans had slaughtered the megafauna and therefore they’d sort of run out of food, and that precipitated, in many places, a switch to agriculture,” he says.

Although the debate is far from settled, it appears ancient humans took thousands of years to wipe out species in a way modern humans would do in decades. Fast forward to today and we are not just killing megafauna but destroying whole landscapes, often in just a few years. Farming is the primary driver of destruction and, of all mammals on Earth, 96% are either livestock or humans. The UN estimates as many as one million plant and animal species are at risk of extinction.

And that’s on top of what we’ve already driven to extinction.

The word seems to have gotten out at last that when trans people demand trans rights we need to get them to specify what rights. I said as much to Dr Finn Mackay and then saw that so had many other people.

What rights? What rights does Mackay mean? What rights do trans people not have?

I counted 12 more replies saying the same thing and then stopped counting.

Of course Mackay hasn’t answered.

London Fire Brigade institutionally misogynist and racist:

London Fire Brigade is “institutionally misogynist and racist”, according to a damning review into its culture.

A black firefighter had a noose put by his locker, while a female one received video of a colleague exposing himself.

Hey you know what other London institution is misogynist (and we might as well assume racist too) according to report? The police. So, that’s great.

The independent review was established by the London Fire Commissioner after a trainee firefighter took his own life in August 2020.

…

The review, conducted by the former Chief Crown Prosecutor for north-west England, Nazir Afzal, concludes that unless the “toxic culture” is tackled then other firefighters will take their own lives.

At some fire stations men huddle around a screen to watch porn.

Talking to the BBC, Mr Afzal said the report made for “grim reading”.

“We’ve heard example after example about women who were harassed or sexually assaulted – constant sexual taunting to the point that I am now saying that the London Fire Brigade is institutionally misogynist,” Mr Afzal said.

They’ve invaded the boys’ club.

“Women told us they were told [by male firefighters]: ‘We want to get you out of here, we don’t want you to be a fire officer.’ It goes back to the whole fireman concept.

“I sat with a very senior female officer who said to me, through tears, that whenever she goes through a dangerous incident, she’s always thinking: ‘Will the men have my back? Will the men around me protect me given how they have treated me back at the station?

“If they feel they can’t trust the men around them because of their behaviour or misbehaviour and worse, then they aren’t safe and neither are we.”

The report also found that while there was often “considerable sensitivity” in the brigade around issues of race, there appeared to be “a worrying blind spot” concerning misogyny and sexism.

That “worrying blind spot” is everywhere. Absolutely everywhere. People rant and rave about “transphobia” and racism while never breathing a word about misogyny. Women just don’t count somehow. Is it because there are so many of us? We’re roughly half the population so how bad can it be? Is that it? Or we’re roughly half the population so that’s just way too much work so let’s focus on literal minorities, like, biting off no more than we can chew type of thing?

One firefighter told the review that she advised her female friends not to let male firefighters in the house to give safety advice because “they go through women’s drawers looking for underwear and sex toys”.

Great. Keep that in mind, should your toaster go up in flames.

So now the LibDems have a new definition of transphobia and the loonies are Leaving the Party.

A number of LGBT+ Liberal Democrats are quitting the party after a formal definition of transphobia was leaked online. A statement, later formally released during Trans Awareness Week, said it was revised due to “greater clarity to the interpretation of the law in this area.”

That is, two lawyers told them their definition is illiberal crap.

Available on the Liberal Democrats website, the new definition rejects “prejudice and discrimination based upon race, ethnicity, caste, heritage, class, religion or belief, age, disability, sex, gender identity or sexual orientation.” However, the new statement added that “Holding and expressing gender critical views, whether in internal debates or publicly, is protected by law”, upsetting many LGBT+ Lib Dems, according to PinkNews.

It’s not illegal to think men are not women, and people who call themselves liberal are upset by this. You couldn’t make it up.