As I mentioned at some point, I didn’t like Hilary Mantel’s two Thomas Cromwell novels, as much of them as I read – I began skipping and skimming quite soon with both. But as so often, I do like her essayistic writing, at least as manifested in this talk published by the London Review of Books. It’s sharp, funny, vivid, specific, insightful, witty – it’s just dang good.

It’s about royal bodies, especially those of royal women. Marie Antoinette, Diana, Our Own Dear Queen, Anne Boleyn, Our Own Dear Kate.

And then the queen passed close to me and I stared at her. I am ashamed now to say it but I passed my eyes over her as a cannibal views his dinner, my gaze sharp enough to pick the meat off her bones. I felt that such was the force of my devouring curiosity that the party had dematerialised and the walls melted and there were only two of us in the vast room, and such was the hard power of my stare that Her Majesty turned and looked back at me, as if she had been jabbed in the shoulder; and for a split second her face expressed not anger but hurt bewilderment. She looked young: for a moment she had turned back from a figurehead into the young woman she was, before monarchy froze her and made her a thing, a thing which only had meaning when it was exposed, a thing that existed only to be looked at.

And I felt sorry then. I wanted to apologise. I wanted to say: it’s nothing personal, it’s monarchy I’m staring at. I rejoined, mentally, the rest of the guests. Now flunkeys were moving among us with trays and on them were canapés, and these snacks were the queen’s revenge. They were pieces of gristly meat on skewers. Let’s not put too fine a point on it: they were kebabs. It took some time to chew through one of them, and then the guests were left with the little sticks in their hands. They tried to give them back to the flunkeys, but the flunkeys smiled and sadly shook their heads, and moved away, so the guests had to carry on the evening holding them out, like children with sparklers on Guy Fawkes night.

I love the flunkeys sadly shaking their heads. I love the guests having to stand around with splintery skewers in their hands. I love the cannibal staring.

Later she moves on to Anne and Henry.

It’s no surprise that so much fiction constellates around the subject of Henry and his wives. Often, if you want to write about women in history, you have to distort history to do it, or substitute fantasy for facts; you have to pretend that individual women were more important than they were or that we know more about them than we do.

But with the reign of King Bluebeard, you don’t have to pretend. Women, their bodies, their reproductive capacities, their animal nature, are central to the story. The history of the reign is so graphically gynaecological that in the past it enabled lady novelists to write about sex when they were only supposed to write about love; and readers could take an avid interest in what went on in royal bedrooms by dignifying it as history, therefore instructive, edifying. Popular fiction about the Tudors has also been a form of moral teaching about women’s lives, though what is taught varies with moral fashion. It used to be that Anne Boleyn was a man-stealer who got paid out. Often, now, the lesson is that if Katherine of Aragon had been a bit more foxy, she could have hung on to her husband. Anne as opportunist and sexual predator finds herself recruited to the cause of feminism. Always, the writers point to the fact that a man who marries his mistress creates a job vacancy. ‘Women beware women’ is a teaching that never falls out of fashion.

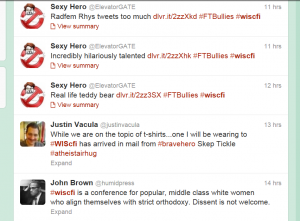

But never mind all that fine writing – the point is, she dissed Kate. Focus on that! Hadley Freeman gets us caught up.

Two weeks ago, Mantel gave a lecture at the British Museum, organised by the London Review of Books. Not, one might have thought, an event ripe with potential for scandal. Nonetheless, scandal issued forth most biliously (if somewhat belatedly) when someone on Fleet Street noticed that Mantel’s speech had been published on the LRB website six days ago and that it contained – clutch your handkerchiefs to your mouths, readers! – comments about Kate, the Duchess of Somethingorother. These comments, incidentally, made (with Mantel’s characteristic subtlety and grace) the patently obvious points that Kate’s entire raison d’être now, in the eyes of the media and the royal family, is to be admired and to breed, just as Anne Boleyn’s had been. She has been embraced by the royal family because she seems like the anti-Diana; one who is not interested in her own publicity but is instead depicted by the royal press machine as safe and devoted to her husband and duties.

Yes but who gave Hilary Mantel permission to say so? That’s the important thing. It’s not how apt her comments are or how well she put them, it’s who said she was allowed to. You have to get permission to say things about the royals. Or you don’t, really, but it’s fun to pretend it’s naughty to do it, especially when it’s a woman doing it.

None of these observations is new, although rarely have they been better couched. They also took up a total of four paragraphs in a 30-paragraph speech – less than one-seventh, in other words – that otherwise focused on Mantel’s very perceptive observations of Henry VIII, the Queen and the nature of monarchy as a whole. But none of these can be illustrated with a photo of the eternally photogenic duchess and, more importantly, none can be souped up into some kind of non-existent squabble between two high-profile women (Boleyn being, famously if rather inconveniently, dead.) So it was Mantel’s “vicious, venomous” and “withering”“rants” and “attacks” on the Duchess that made the front pages of today’s Mail and Metro papers, as well as getting a prominent mention in the Independent and a somewhat smaller one in the Guardian. This kind of extrapolation is reminiscent of when a critic describes a film as “astonishingly bad” and the film poster then claims the critic described it as “astonishing!”

Catfight! Catfight! Bitchez be fighting!

It is worth looking at what is going on here. Lazy journalism, clearly, and raging hypocrisy, obviously: what has any paper done with Kate for the past decade but use her as decorative page filler? Indeed, when the BBC covered Mantelgate (Mantelpiece?) it included lingering shots of the duchess’s fair form while quoting in horror from Mantel’s speech about the royal women existing to be admired. This is also a good example of how the Mail fights back when it feels it is being attacked. For if Mantel was attacking anyone in her talk, then her aim was clearly at the Mail with its obsessive, prurient fascination with Kate. To see the Mail gasping at Mantel’s suggestion that the duchess is “designed to breed” when it has been on “bump watch” since she walked down the aisle is the Fleet Street reenactment of Captain Renault in Casablanca proclaiming himself to be “shocked to find gambling is going on here” while collecting his winnings. It then added helpfully that Mantel is “infertile” and “dreams of being thin”. Yeah, no wonder she’s jealous of our Kate, the fat childless cow.

Old ugly woman disses young pretty woman! Catfight! Bitchez be fighting!

But the liberal press has been arguably just as bad, with the Independent providing a kindly list, allowing readers to compare “the author and the princess”, again emphasising Mantel’s weight. The subject of women talking about women has become as fraught an issue for the left as it is for the right. The conservative press loves a good woman v woman – or “author v princess” – fight because it suggests that women are all hysterical girlies who can’t be trusted with proper grownup issues because they’ll start throwing tampons at one another…

On the liberal side, one of the tenets of the fourth wave of feminism, which is just starting to crest, is that women should not criticise one another’s life choices…

Mantel was discussing how the royal family and the media manipulate women; it is of little surprise that the media would attack her back. But this nonsense highlights how it is still, apparently, impossible to be a woman and put forth a measured opinion about one of your own without it being twisted into some kind of screed-ish, unsisterly attack. As Mantel has learnt to her cost today, it’s not only royal women who are expected to stay quiet.

Because if women don’t stay quiet, we’ll all go deaf from the catfights.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)