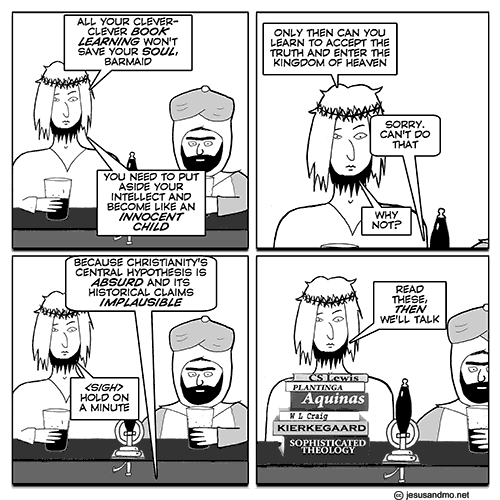

Jesus recommends child-like faith to the barmaid. The barmaid is less than eager to comply.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

Jesus recommends child-like faith to the barmaid. The barmaid is less than eager to comply.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

A reminder – if you haven’t already, please sign the petition asking the Obama admin to call on Indonesia to free Alexander Aan. And above all please pass it on – via Twitter, Facebook, reddit, all those other thingies that I don’t even know the names of which (ok I know the name of tumblr), blogs, friends, networks, everything. It has to get 25,000 signatures by August 16th, so spreading the word is urgent.

Most people have no trouble signing but a few do. I did, I got a silly message saying there had been too many attempts to sign in from my IP address, which made no sense, since there hadn’t been any. But they sent me a new password with no fuss, so if you get a hassle just swallow your irritation and jump through the hoops. We can’t expect the White House to make it easy for us to sign their petitions, now can we! [mutter mutter democracy mutter]

Dooooooo eeeeeeeeeeet. Thank you.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

On a more cheerful note – following a pingback here yesterday led me to one venomous anti-me post which included a link to another venomous anti-me post which included a link to a post by someone with a different take. I will share some of it with you because it is pleasant and it is nice to have pleasant things in among all the venom. Also the author said it’s a message to some people and she wants to get it out there, so I’m helping her get it out there.

Somewhere along the line I found links to some blog posts about the Women in Secularism conference and reading them was just so inspiring. Since I realised/accepted/announced to myself that I was an atheist, I have had some interest in listening to/chatting to others who feel the same way. Hence the Atheist Experience. But the blogs from the WIS conference got me excited to get more involved in a way that nothing else had. I imagined what it might have been like to have been there. And after watching some of the talks on YouTube it was reinforced that it would have been a really inspiring environment to be at. The videos are inspiring enough and have me thinking about how best to make a difference from my little corner of the world.

See what I mean? That was very pleasant to read, after a week filled with shouting.

So of course I have become aware of this whole discussion on sexual harassment and policies at conferences, etc, etc. And the thing is, I have been really pleased and impressed at the way most of the people I have seen in the community have approached the issue. Women like Ophelia Benson, Rebecca Watson, Jen McCreight and Greta Christina as well as men like PZ Myers, Jason Thibeault and others, who, from what I can see have done nothing but be up front, thoughtful and honest and, most importantly in my opinion, refused to back away from dealing with the important issues even when others have made, or at least tried to make, things really difficult for them.

Anyway, what really triggered this post was that this was linked on my feed this morning and I guess I really just want all the people at FreeThought Blogs and Skepchick to know that there are people out there, and maybe a lot more than you know, that *do* appreciate you all continuing to push forward on these important issues and that some people, like myself, actually feel more inclined to want to try and attend one of these events some day, or at least begin to participate more in the online community, knowing that there are people out there working hard to make it safe to do so.

So yeah, mainly, thank you for doing what you do and keep doing it.

[waving vigorously] Thanks back, and will do, and welcome to the network.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

When the ladies returned to the drawing room, there was little to be done but to hear Lady Catherine talk, which she did without any intermission till coffee came in, delivering her opinion on every subject in so decisive a manner as proved that she was not used to have her judgment controverted. She enquired into Charlotte’s domestic concerns familiarly and minutely, and gave her a great deal of advice as to the management of them all; told her how every thing ought to be regulated in so small a family as her’s, and instructed her as to the care of her cows and her poultry. Elizabeth found that nothing was beneath this great lady’s attention, which could furnish her with an occasion of dictating to others. In the intervals of her discourse with Mrs. Collins, she addressed a variety of questions to Maria and Elizabeth, but especially to the latter, of whose connections she knew the least, and who, she observed to Mrs. Collins, was a very genteel, pretty kind of girl. She asked her at different times, how many sisters she had, whether they were older or younger than herself, whether any of them were likely to be married, whether they were handsome, where they had been educated, what carriage her father kept, and what had been her mother’s maiden name? — Elizabeth felt all the impertinence of her questions, but answered them very composedly. — Lady Catherine then observed,

“Your father’s estate is entailed on Mr. Collins, I think. For your sake,” turning to Charlotte, “I am glad of it; but otherwise I see no occasion for entailing estates from the female line. — It was not thought necessary in Sir Lewis de Bourgh’s family. — Do you play and sing, Miss Bennet?”

“A little.”

“Oh! then — some time or other we shall be happy to hear you. Our instrument is a capital one, probably superior to — You shall try it some day. — Do your sisters play and sing?”

“One of them does.”

“Why did not you all learn? — You ought all to have learned. The Miss Webbs all play, and their father has not so good an income as your’s. — Do you draw?”

“No, not at all.”

“What, none of you?”

“Not one.”

“That is very strange. But I suppose you had no opportunity. Your mother should have taken you to town every spring for the benefit of masters.”

“My mother would have had no objection, but my father hates London.”

“Has your governess left you?”

“We never had any governess.”

“No governess! How was that possible? Five daughters brought up at home without a governess! — I never heard of such a thing. Your mother must have been quite a slave to your education.”

Elizabeth could hardly help smiling, as she assured her that had not been the case.

“Then, who taught you? who attended to you? Without a governess you must have been neglected.”

“Compared with some families, I believe we were; but such of us as wished to learn, never wanted the means. We were always encouraged to read, and had all the masters that were necessary. Those who chose to be idle, certainly might.”

“Aye, no doubt; but that is what a governess will prevent, and if I had known your mother, I should have advised her most strenuously to engage one. I always say that nothing is to be done in education without steady and regular instruction, and nobody but a governess can give it. It is wonderful how many families I have been the means of supplying in that way. I am always glad to get a young person well placed out. Four nieces of Mrs. Jenkinson are most delightfully situated through my means; and it was but the other day that I recommended another young person, who was merely accidentally mentioned to me, and the family are quite delighted with her. Mrs. Collins, did I tell you of Lady Metcalfe’s calling yesterday to thank me? She finds Miss Pope a treasure. “Lady Catherine,” said she, “you have given me a treasure.” Are any of your younger sisters out, Miss Bennet?”

“Yes, Ma’am, all.”

“All! — What, all five out at once? Very odd! — And you only the second. — The younger ones out before the elder are married! — Your younger sisters must be very young?”

“Yes, my youngest is not sixteen. Perhaps she is full young to be much in company. But really, Ma’am, I think it would be very hard upon younger sisters, that they should not have their share of society and amusement because the elder may not have the means or inclination to marry early. — The last born has as good a right to the pleasures of youth, as the first. And to be kept back on such a motive! — I think it would not be very likely to promote sisterly affection or delicacy of mind.”

“Upon my word,” said her ladyship, “you give your opinion very decidedly for so young a person. — Pray, what is your age?”

“With three younger sisters grown up,” replied Elizabeth smiling, “your Ladyship can hardly expect me to own it.”

Lady Catherine seemed quite astonished at not receiving a direct answer; and Elizabeth suspected herself to be the first creature who had ever dared to trifle with so much dignified impertinence!

http://www.pemberley.com/janeinfo/ppv2n29.html

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

There was a good piece on NPR last week about stereotype threat, by Shankar Vedantam.

It starts with the STEM problem: fewer women in science, engineering, technology and mathematics. It’s a bad thing. It matters.

It isn’t just that fewer women choose to go into these fields. Even when they go into these fields and are successful, women are more likely than men to quit.

And that isn’t because they get bored and decide to spend all their time thinking about shoes instead.

Audio sampling reveals that something else is going on.

When female scientists talked to other female scientists, they sounded perfectly competent. But when they talked to male colleagues, Mehl and Schmader found that they sounded less competent.

One obvious explanation was that the men were being nasty to their female colleagues and throwing them off their game. Mehl and Schmader checked the tapes.

“We don’t have any evidence that there is anything that men are saying to make this happen,” Schmader said.

But the audiotapes did provide a clue about what was going on. When the male and female scientists weren’t talking about work, the women reported feeling more engaged.

For Mehl and Schmader, this was the smoking gun that an insidious psychological phenomenon called “stereotype threat” was at work. It could potentially explain the disparity between men and women pursuing science and math careers.

Women have to worry about it, and men don’t.

For a female scientist, particularly talking to a male colleague, if she thinks it’s possible he might hold this stereotype, a piece of her mind is spent monitoring the conversation and monitoring what it is she is saying, and wondering whether or not she is saying the right thing, and wondering whether or not she is sounding competent, and wondering whether or not she is confirming the stereotype,” Schmader said.

All this worrying is distracting. It uses up brainpower. The worst part?

“By merely worrying about that more, one ends up sounding more incompetent,” Schmader said.

What to do? Change the stereotype.

Mehl and Schmader said the stereotype threat research does not imply that the gender disparity in science and math fields is all “in women’s heads.”

The problem isn’t with women, Mehl said. The problem is with the stereotype.

The study suggests the gender disparity in science and technology may be, at least in part, the result of a vicious cycle.

When women look at tech companies and math departments, they see few women. This activates the stereotype that women aren’t good at math. The stereotype, Toni Schmader said, makes it harder for women to enter those fields. To stay. To thrive.

“If people like me aren’t represented in this field, then it makes me feel like it’s a bad fit, like I don’t belong here,” she said.

Shirley Malcom, a biologist who heads education programs at the American Association for the Advancement of Science calls it a chicken and egg problem: “The fact that there are maybe small numbers in some areas keeps the numbers down.”

It may sound like a Zen riddle, but Malcom, Schmader and Mehl’s solution to the problem of stereotype threat in science, technology and engineering is actually simple.

In order to boost the numbers of women who choose to go into those fields, you have to boost the number of women who are in those fields.

This is one (big) reason you can’t just do it by yourself by out-toughing everyone else. You also shouldn’t have to, but in any case, you can’t.

So bullying, jeering, blaming, othering, and mocking are not helpful either. Telling us not to be so sensitive? Also not useful. You can’t just decide to rise above it – it doesn’t work.

Now, most scientists say they don’t believe the stereotype about women and science, and argue that it won’t affect them. But the psychological studies suggest people are affected by stereotype threat regardless of whether they believe the stereotype.

The way to fix it is to fix it. Not sneer at it, not shrug it off, not tell people to suck it up – but to fix it.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

I thought that was the last of it, but there’s this adorable song that was performed at TAM.

Dedicated to James Randi, JREF, and all clear-thinking individuals who are fond of dirty words.lyrics

He said “Come up for coffee”Before she reached her floorNow, some folks who have vaginas don’t show up here anymoreWell, perhaps that guy was wrongBut can’t we all just get along?Now, Professor Richard DawkinsSaid, “Really, what’s the harm?He never put his cock in or even touched your arm.”Well, even smart guys get stuff wrongCan’t we all just get along?

Soon the blogosphere went ape-shitAnd that ape-shit hit the fanSome cried, “Hey gals, just chill out,” and some said “Kill the man!”We all stood our moral high ground,Using 20-dollar wordsLots of people talkin’But nobody bein’ heardYes, Dawkins was a dick,And he shouldn’t get a passBut honestly, some chicks should pull the sticks out of their assIt’s not the weak against the strongIt’s not Fay Wray against King KongI heard last year some girls got grabby With Paul Provenza’s schlong!But here’s the point of this whole song:Can’t we all just get along?

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

Prepare to be astonished.

Consumers could be wasting their money on sports drinks, protein shakes and high-end trainers, according to a new joint investigation by BBC Panorama and the British Medical Journal.

The investigation into the performance-enhancing claims of some popular sports products found “a striking lack of evidence” to back them up.

Surely not! Surely the more expensive a shoe is, the faster you can run when you wear it. You would think so, but the BBC says alas, we have been deceived.

A team at Oxford University examined 431 claims in 104 sport product adverts and found a “worrying” lack of high-quality research, calling for better studies to help inform consumers.

But not Lucozade, I’m sure. Of course that totally works.

In the case of Lucozade Sport, the UK’s best-selling sports drink, their advert says it is “an isotonic performance fuel to take you faster, stronger, for longer”.

Dr Heneghan and his team asked manufacturer GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) for details of the science behind their claims and were given what he said scientists call a “data dump” – 40 years’ worth of Lucozade sports research which included 176 studies.

Dr Heneghan said the mountain of data included 101 trials that the Oxford team were able to examine before concluding: “In this case, the quality of the evidence is poor, the size of the effect is often minuscule and it certainly doesn’t apply to the population at large who are buying these products.”

But it probably doesn’t actually make people weaker or slower – so that should be good enough. GlaxoSmithKline has to make a living you know. Lighten up.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

The Catholic church in the UK is finding itself having to answer to the law. What an indignity! What presumption! Mere secular humans with secular training in secular law daring to meddle with sanctified Standers-in For Jesus. The church is god’s telephone line! Don’t these presumptuous mundane unholy law-botherers realize that? How dare they haul a bunch of priests to court?

A landmark hearing at the Supreme Court in London on Monday will consider who is responsible for compensating victims of child abuse by Catholic priests.

The case is being brought by 170 men who allege that they were sexually and physically abused at a Roman Catholic children’s home.

The High Court at Leeds and the Court of Appeal have already decided that the Roman Catholic Diocese of Middlesbrough is responsible for compensating victims of child abuse at the St William’s children’s home, Market Weighton, East Yorkshire, between 1960 and 1992.

On account of the former principal of that children’s home was found guilty of sexually assaulting 22 boys, some as young as 12. Did the church cry out in compassionate anguish and rush to do everything it could to compensate? No it did not. It did the other thing.

Compensation proceedings on behalf of claimants were started in 2004. Although two Roman Catholic organisations were involved in running the St William’s children’s home, both organisations have attempted to use legal technicalities to escape responsibility, a tactic mirrored in other Catholic child abuse cases.

Despite a series of shocking examples of Catholic priests being convicted over the past decade, the Catholic Church continues to argue that it is not responsible for abuse committed by its priests and officials. In the most recent example the Roman Catholic Bishop of Portsmouth attempted to argue that he was not responsible for compensating a victim of abuse by a priest named Father Baldwin, on the basis that he did not employ him but simply allowed him ministry in his Diocese. Unsurprisingly on 12th July 2012 the Court of Appeal decided that the Bishop was indeed responsible.

You see, this is that problem again – the fact that they constantly claim to be morally better than the rest of humanity, because of their churchness – their adherence to “church teachings” – when in fact they’re selfish self-protecting shits. They’re not compassionate, they’re not generous, they’re not other-regarding – they’re not good.

They seem to think nobody can see this. We can see it.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

But Giles Fraser looks quite thoughtful compared to Ed West in the Telegraph.

…people are not naturally moral relativists, and female circumcision cannot be viewed in any way as an acceptable cultural practice, violating all Western ethical principles, scarring women for life out of sheer spiteful misogyny.

But it’s inevitable that any movement that has been proved right and principled will then push its ideology too far until it too becomes intolerant and ludicrous, and the campaign against male circumcision is just one example. In theory removing a foreskin could be seen as a violation of a child’s rights, but that’s to take a theoretical liberal argument to an absurd and illiberal position. It equates genuinely horrific and immoral alien cultural practices with simply strange ones, which almost becomes an extreme reverse cultural relativism – all cultures that aren’t mine are equally bad.

Absurd and illiberal? To tell parents they can’t snip off a bit of their baby’s penis just because it’s supposed to be a religious obligation? Come on. I can see saying there are tensions, but to blow off the issue that easily is…well, absurd and illiberal.

Of course most people are not saying that circumcision is anywhere as bad as FGM, but that it does mutilate the child and so violate individual rights…But liberalism should mean distinguishing between abusive, unacceptable cultural forms that violate individual freedom and ones you just don’t agree with (which, to some New Atheists, is going to mean pretty much all religious upbringings).

Yes but in what sense is it clear that snipping off a bit of a baby’s penis for non-medical reasons is not an abusive, unacceptable cultural form that violates individual freedom?

I would disagree with Fraser over only one thing – calling this liberalism. It’s actually statism, an ideology that causes far more child cruelty than all the religions in Europe combined.

Ah right, it’s the fault of New Atheism and statism. That’s that sorted.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

Giles Fraser is angry about the German court decision that religious circumcision of infants is a violation of their right to bodily integrity (although he doesn’t say that, but substitutes “against the best interests of the child”). He’s outraged that Merkel had to say ”I do not want Germany to be the only country in the world in which Jews cannot practise their rites.”

Yet the circumcision of babies cuts against one of the basic assumptions of the liberal mindset. Informed consent lies at the heart of choice and choice lies at the heart of the liberal society. Without informed consent, circumcision is regarded as a form of violence and a violation of the fundamental rights of the child. Which is why I regard the liberal mindset as a diminished form of the moral imagination. There is more to right and wrong than mere choice.

Well there’s a non sequitur. Of course there’s more to right and wrong than mere choice, but when it’s a matter of snipping off a bit of the penis for purely religious reasons then informed choice really is preferable to its absence.

He was circumcised at eight days old. His son wasn’t. He regrets that.

I still find it difficult that my son is not circumcised. The philosopher Emil Fackenheim, himself a survivor of Sachsenhausen concentration camp, famously added to the 613th commandments of the Hebrew scriptures with a new 614th commandment: thou must not grant Hitler posthumous victories. This new mitzvah insisted that to abandon one’s Jewish identity was to do Hitler’s work for him. Jews are commanded to survive as Jews by the martyrs of the Holocaust. My own family history – from Miriam Beckerman and Louis Friedeburg becoming Frasers (a name change to escape antisemitism) to their grandson becoming Rev Fraser (long story) to the uncircumcised Felix Fraser – can be read as a betrayal of that 614th commandment.

And I have always found this extremely difficult to deal with. On some level, I feel like a betrayer.

I can sympathize with that – but what he’s overlooking (rather distastefully, when you look closely) is that that’s about him, and that it doesn’t give him the right to snip off a bit of his infant’s penis. His son could still get circumcised – but it would be his decision, about his body. It seems to me it’s a good deal more of a betrayal to force that decision on someone else.

As I argued in this week’s Church Times, one of the most familiar modern mistakes about faith is that it is something that goes on in your head. This is rubbish. Faith is about being a part of something wider than oneself. We are not born as mini rational agents in waiting, not fully formed as moral beings until we have the ability to think and choose for ourselves. We are born into a network of relationships that provide us with a cultural background against which things come to make sense. “We” comes before “I”. We constitutes our horizon of significance. Which is why many Jews who consider themselves to be atheists would still consider themselves to be Jewish. And circumcision is the way Jewish and Muslim men are marked out as being involved in a reality greater than themselves.

Yes, but, again – that shouldn’t be forced.

I know what the problem with that is. If it’s not “forced” – if it’s not the child’s world from the first moment – then the roots are much shallower. It’s not such an embracing “we.” Lots and lots of parents – probably most – want that embracing “we.”

But then, most people don’t get enough exposure to a “shallower” kind of we, which makes possible an expanding and exciting set of “we”s as the child matures. Informed choice really is a pretty good idea.

H/t Tauriq M

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

Ghaffar Hussain talks to Alom Shaha in The Commentator. Alom’s book The Young Atheist’s Handbook launches tomorrow, or launched yesterday, or last week (launches get confusing – they migrate).

Alom points out that he’s had different experiences from the horsemen, and he wants to show that atheism isn’t just for horsemen. Why promote atheism?

I believe that lots of people only follow a religion because of parental and cultural pressure and that they would be happier if they could be true to themselves and lead godless lives. Belief in god is not something that comes naturally to all of us; many of us find it impossible to believe in god and it can be liberating and life-enhancing to fully embrace this lack of belief and live our lives without religion.

Open the door.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

There’s a very informative comment on Pamela Gay’s talk, by “Stella Luna.”

I was unable to attend TAM this year due to my work schedule, but I very much wanted to go because I enjoy it so much – and also to be another woman in the crowd. While I personally have not experienced a grab or offensive comment at TAM, I will absolutely make it clear that as a very experienced mid-level manager at the Fortune 500 company I work for, I am the target of off-color remarks, double entendres, “praise” for my skills that might add praise for my wearing a skirt that day, or even unwelcome hugs in lieue of handshakes from the program director. (I’ve yet to see the Chief Engineer receive a hug from the director…)

When it isn’t about me, it’s about some other woman. It’s public, and it’s always just right below the level of out and out harassment by being a joke, a chuckle, a good-natured little ribbing. You know, because we trust each other and all… But it is NEVER a joke made by us women, and never a joke made about a man or about a person’s religion or skin color or country of origin. It is the last haven for obnoxiousness.

My company spender millions of dollars a year on high-profile internal marketing campaigns about Respect, about Diversity, and about Inclusion – the payoff is meant to be higher retention rates of skilled employees and lower hiring and training expense overall. But I think we need to get much more specific about the “woman problem” because it isn’t sinking in that those little humorous punch lines are a significant source of anger, discomfort and reduced morale to those of us who, as a percentage of our baseline, are the most likely to leave this company.

And by the way, I have pointed out very directly to trusted male colleagues who DON’T behave this way that they are still part of the problem by looking away and being silent when it occurs. It is up to them, just as it is up to me, to at least have a side conversation later with the perpetrator and point out how their behavior conflicts with the company policies as well as basic decency. Peer pressure works; let’s harness it for the common welfare.

A significant source of anger, discomfort, reduced morale, and stereotype threat. All those little digs day after day, year after year, drip drip drip, are why members of despised groups are subject to stereotype threat. They’re not “just” annoying, they do damage. It’s seriously stupid (as well as wicked) to damage people (and their abilities and hence everyone’s overall prosperity and well-being) for the sake of a joke combined with a sense of superiority.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

Kausik Datta has an incisive post on Ayesha Nusrat’s op-ed in the New York Times about how liberating it is to submit to a religious obligation to wrap your head and neck in a large bandage.

Clearly, to Ms. Nusrat, the hijab is merely a few yards of cloth. For far too many women in far too many countries (for instance, the Middle East, North Africa, Far East and the Southeast of Asia, not to mention, Europe), the hijab is an obligatory article of indenturement that permits no choice, but is to be worn on pain of punishment and/or death; to them, it is a symbol of systematic oppression.

A symbol and the reality, which is why it’s so infuriating when people try to dress it up as the opposite. A putative religious obligation can’t be liberating.

Has Ms. Nusrat ever considered how/why Islamic fundamentalists (be it Taliban, or Boko Haram, or the regime in Iran) ALWAYS impose the hijab, burqa or niqab on women at the first opportunity? Why does she think that is?

Because Islamic fundamentalists want to liberate women! Wait…

I find it odd that it seems to have never struck Ms. Nusrat that these inviolable mandates to cover up reflect the bleak reality of so many women’s lives. She glibly talks about a ‘misconception that Muslim women lack the strength, passion and power to strive for their own rights’; she frames it wrongly. As women, the Muslim women lack nothing; they are just as strong and passionate about striving for their own rights as women anywhere else. But Islam is something else. Islam, especially fundamentalist Islam, actively denies them the power, and would rather beat the women into submission than relinquish control – and that is not a misconception, judging by the experience of many, many women in the world. If Ms. Nusrat continues to dismiss their experience because of her beliefs, she is being dishonest.

Read the whole thing. It’s admirably indignant.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

Richard Dawkins asked a very interesting question on Twitter a couple of days ago (so I’m sure he wants our input).

Writing my autobiography and struggling to find the right balance. How much personal stuff to put in, how much purely intellectual memoir?

I say more of the latter than the former. 70/30, maybe.

Intellectual is personal to people who care about intellectual matters, so making it mostly intellectual needn’t mean it’s dry or Spockian. Mill’s autobiography is fascinating. So is Gibbon’s. And then, the point of RD is the intellectual stuff, so it makes sense not to skimp on it.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

Be sure you don’t miss Taslima’s post on acid attacks on women – unless you can’t stand it: warning: it is horrific; the pictures are horrific.

It’s terrible to look at the pictures and realize people must know this is what acid does, and that’s why they do it.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

You know that T shirt that Harriet Hall wore?

This is the back view

She wore it three days in a row, at least. My source didn’t see her on the fourth, but it seems likely she wore it then too.

I don’t understand this. I don’t understand people.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

Kristjan Wager has a good post on the Deep Rifts. He’d rather have the rifts than no rifts at the price of entrenched sexism.

So, to sum it up, there are deep rifts in the movement, and I think it is fine. Not only that, I feel more comfortable being in a smaller community within the movement, which doesn’t include people whose opinions and behavior I find repugnant. I can still appreciate the good work done by those people (like I did with e.g. Hitchens) without wanting to be part of the same community.

Fewer but better Russians. (I kid, I kid.)

Massimo Pigliucci also has a good post, although he does do the “both sides” thing, which given what a big chunk of the other side is like, really isn’t as reasonable as it might sound to a novice.

Oh wait, no he doesn’t, or at least he clarifies in a comment that that’s not what he meant. I’ll leave the above paragraph because there are people who think that is what he meant, so this will perhaps help.

Here’s his clarification:

there may be a misunderstanding here about what my call for moderation concerns. Of course there is no moderate position to be held about sexism (or racism, for that matter): it’s bad, period.

But there is moderation to be called for in how we talk and act about it. The example in question here, discussed by Russell Blackford in the post I linked to above, is AA’s overly reaching “no-hugs” policy, which – it can be argued – doesn’t really address the actual issue and potentially undermines a sense of community by attempting to over-regulate normal human interactions.

Sure. Specifics can be discussed, calmly and reasonably. (I’ve been staying out of those discussions, because honestly I don’t know enough about the subject to have a useful opinion. I was invited to participate in the conference call with American Atheists to discuss their policy, but I wasn’t available at the right time – which is just as well.) Specifics can be discussed, calmly and reasonably – which includes not calling people Talibanesque or Femistasi.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

A young woman finds an exciting new path to liberation. She takes to wearing the hijab.

…before you race to label me the poster girl for oppressed womanhood everywhere, let me tell you as a woman (with a master’s degree in human rights, and a graduate degree in psychology) why I see this as the most liberating experience ever.

We know. You’re taking control, you’re being seen for who you really are instead of as a female human being with hair and a neck.

My experience working as a Faiths Act Fellow for the Tony Blair Faith Foundation and dealing with interfaith action for social action brought me more understanding and appreciation of various faiths. I found that engaging in numerous interfaith endeavors strengthened my personal understanding about my own faith.

Do you think she uses the word “faith” enough times in that passage? Maybe a few hundred more would get her point across better?

Tony Blair, you have a lot to answer for.

I am abundantly aware of the rising concerns and controversies over how a few yards of cloth covering a woman’s head is written off as a global threat to women’s education, public security, rights and even religion. I am also conscious of the media’s preferred mode of portraying all hijabi women as downtrodden and dominated by misogynist mullahs or male relatives who enforce them into sweltering pieces of oppressive clothing. But I believe my hijab liberates me.

Despite the reality of the misogynist mullahs and the conservative male relatives – she “believes” the hijab liberates her, and faith can move mountains, so there you go.

For someone who passionately studied and works for human rights and women’s empowerment, I realized that working for these causes while wearing the hijab can only contribute to breaking the misconception that Muslim women lack the strength, passion and power to strive for their own rights.

No, that’s not accurate – that “only” is wrong. Working for women’s rights while wearing the hijab can also for instance send the message that you’re confused, or that your religion trumps your commitment to women’s rights, or other possibilities that you probably don’t like.

In a society that embraces uncovering, how can it be oppressive if I decided to cover up? I see hijab as the freedom to regard my body as my own concern and as a way to secure personal liberty in a world that objectifies women. I refuse to see how a woman’s significance is rated according to her looks and the clothes she wears. I am also absolutely certain that the skewed perception of women’s equality as the right to bare our breasts in public only contributes to our own objectification. I look forward to a whole new day when true equality will be had with women not needing to display themselves to get attention nor needing to defend their decision to keep their bodies to themselves.

Uh huh, but the hijab isn’t the opposite of baring your breasts, it’s the opposite of baring your hair and neck. Different thing. It’s very easy to refrain from baring your breasts without putting on a hijab. There are lots of ways you can attempt to secure personal liberty in a world that objectifies women without wearing a hijab, and wearing one is in many ways a very bad way to attempt to secure personal liberty.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

A longish time ago we talked about the idea of doing book discussion threads, or was it Shakespeare threads. One of those. Inspired by Pamela Gay’s urgings to make the world better and do something, let’s get to it.

Let’s start at the top, with Hamlet.

We’ll talk until no one has anything left to say.

I’ll start.

Biggest thing: it’s not [just, or primarily] about A Guy Who Can’t Make Up His Mind. That’s become the boring soundbite about it, and it is very damn boring. That’s not what it’s about. It’s about a million things, and that one is more incidental than most of them.

It’s about everything. I think I mentioned when we were talking about Shakespeare before that I once developed a fascination with Hamlet, and spent several months reading/watching/listening to it and related things (the rest of the plays, other playwrights, Elizabethan writers in general, secondary stuff). That’s partly because it’s about everything.

Such as

Love

Betrayal

Time, and the erosion of love over time

Grief and loss, obviously

Revenge

Sex

Family, romance, friendship

Death

Epistemology

Truth

Appearances, and deception (or “seeming” as Shakespeare liked to call it). “A man may smile, and smile, and be a villain.”

Acting

Lies, deceit, trickery

Thinking

Words

—

Your turn.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

Pamela Gay has posted the text of her instantly-famous TAM talk – and oh man is it a stemwinder.

She starts with the bullied school bus monitor, and the people who changed her life in response. She moves on to the 5th grader forbidden to give his winning speech on same-sex marriage, and the internet outcry that made the principal feel compelled to let the student give his speech after all.

She moves on to people getting together to do good things, like “the Virtual Star Parties that my dear friend Fraser Cain hosts and that I and many others participate in.” She talks about hope and despair, dreamers and trolls.

Doing what he does isn’t easy. It’s a lot easier to do nothing… easier to lose hope that anything can even be done. And there are people out there who would encourage despair.

If, like me, you’re a child of the 80s, you may remember a movie called “Neverending Story”. It came out when I was a dorky little kid. This movie contained a certain giant wolf who totally understands trolls and their effect of creating their own great nothing in the world. (link) When asked why he is helping the great nothing destroy their world, this wolf responds, “It’s like a despair, destroying this world. … people who have no hopes are easy to control.”

Looking around the internets, I see a lot of people sitting around trolling, and a lot people experiencing despair. There are YouTube videos of people complaining, and blog posts of people expressing their hurt, and in many cases there are legitimate reasons for people to be upset. There are people dying because we’ve lost herd immunity (link). There are lesbian teens in texas being killed for falling in love (link). There are so many cases of abuse that it hurts to read the news. There are lots of real reasons to be frustrated about the world we live in and it is easy to complain… and it is easy to lose hope.

It is dreaming that is hard.

That makes me choke up rather.

She urges us to change the world, and gives moving examples of people doing that. (They remind me of one she didn’t mention: Wangari Mathai, one of my great heroes.)

She urges us to do amateur astronomy if we want to, and offers helpful tools, such as her own CosmoQuest.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IkA3p_vTo_k

Then she talks about trolls who try to mess all this kind of thing up.

She talks about Anita Sarkeesian. She quotes from that New Statesman piece by Helen Lewis that I quoted from the other day.

And then she gets to the part where she needed real courage to say it.

This talk is one I struggled to write. To finish this talk I have to step out of my comfort zone and give an honest acknowledgement that trolling isn’t something that just happens in nebulous random places on the internet and it isn’t just people being verbal in their close-mindedness. Sometimes things are more physical and more scary. As an astronomer, at professional conferences, I’ve randomly had my tits and ass grabbed and slapped by men in positions of power and by creeps who drank too much. This is part of what it means to be a woman in science. With the creeps I generally hold my own and get them to back off like I would with any asshole in a bar. With the people in power… I commiserate with the other women as we share stories of what has been grabbed by whom. I know as I say this that it sounds unbelievable – and how can we report the unbelievable and expect to be believed?

This isn’t to say women shouldn’t go into astronomy. It is just to say that in the after hours events, you sometimes need to keep your butt to the wall and your arms crossed over your chest.

Some of you have to have power to stop discrimination and harassment. It pisses me off to know that as strong as I am, I know I’m not powerful enough to name names and be confident that I’ll still have a career.

Which is exactly what Jen said – before the mountain of shit hit the fan. Exactly.

It’s often hard for women and minorities to rise to positions of power – to break through that glass ceiling. This is in someways a self-efficacy issue, where the constant down pouring of belittling comments and jokes plays a destructive role in self confidence. At my university, I’ve heard tenured faculty laugh that there is a policy not to hire women into tenure track physics positions. They do this in front of the junior faculty. I’ve heard people joke that the reason I’m in a research center rather than in Physics is because I have boobs. It’s all said with a laugh. So far, its been nothing actionable or against the law. But it hurts, because I know the women who work for me, strong awesome powerful women like the Noisy Astronomer Nicole Gugiliucci and like Georgia Bracey are going to be hearing this, and it is going to effect their self esteem as they look to build their own carreers. I know it hurts my self esteem. And I know there is nothing I can do to change the reality I am in. I could move to another university – I could change which reality I’m in – but that would leave behind a university devoid of women role models who are capable in physics and computer science, the two fields that my students come from. I stay, and I try to be the example of a woman doing things that matter. I try to say Brains, Body, Both – it is possible even in computational astrophysics.

Thank you.

Here in the skeptics community, we, like every other segment of society, have our share of individuals who, given the right combination of alcohol and proximity will grab tits and ass. I’ve had both body parts randomly and unexpectedly grabbed at in public places by people who attend this conference – not at this conference, but by people at this conference. Just like in astronomy, it’s a combination of the inebriated guys going too far – guys I can handle - and of men in power being asses.

I know that there has been a lot of internet buzz over the last two years about these issues. This community is filled with strong women. A Kovacs and MsInformation are two ballsy women I draw inspiration from. These are just two of the many SkepChicks, and many of the Skeptical and scientific podcasts have female hosts. When they see something wrong, they ask for ways to protect people from being hurt. And they do like Surly Amy did and raise money to get women here – women who together can support one another so that when we go home we have a network of women to turn to to support us even at a distance. These are women who react to problems with a sharp word and a needed call to action that is designed to fix the problems

I know this is an uncomfortable topic. An I know that my talk is going to provoke some of you who don’t think I should air dirty laundry. But I see a problem and I can’t change it alone.

Thank you, thank you, thank you.

Changing our society takes all of us. Doing something is being that guy, and I’ve had two different guys be that guy for me, who jumps between the girl and the boob grabber and intervenes. Doing something is donating to get more women here, and to get more minorities here, and making a point to admit, we’ve got problems – we’re humans – and saying Stopping Harressment Starts with me. (see endnote 2, below)

We can make TAM a place that is focused on inspiring skeptical and scientific activism – that is focused on how each of us can in our own way make the world better. We can put this bullshit behind us, and we can try to rise above the problems that plague so many conferences in every field. We can be the better example.

We can make TAM a place that is focused on inspiring skeptical and scientific activism – that is focused on how each of us can in our own way make the world better. We can put this bullshit behind us, and we can try to rise above the problems that plague so many conferences in every field. We can be the better example.

Read the whole thing – I know you will, because you can see from this how good it is, and you know there are more videos and graphics.

I feel a whole lot less isolated now. Pamela rocks.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)