Preamble: This essay focuses on a common source of contention in discussions of accusations of rape. It is understood that for some rape survivors, this article will file under “Too Long – Didn’t Read”, purely for reasons of mental health and self-preservation. An obligatory trigger warning also applies.

It is also understood that for many people, a simple “fuck off!” is the best, and a perfectly justifiable, response to what I am calling ‘The “Good Juror” Pose. I’m tentatively offering my prescription to those best able to help, rather than making expectations of those who have been hurt.

I think there is a need, for those in a position to make a difference, for more reflection on what is actually being said, and on where distinctions and demarcations can be made in order to prevent a lot of unnecessary acrimony.

***

Recent discussions of Woody Allen, and revived accusations levelled against him by Dylan Farrow, have drawn the usual roaches and lice out of the woodwork – specifically, those with an interest in the spoils of providing earnest character references for, and supererogated defences of, the accused.

The presumption of innocence is important for jurors, and for journalists reporting the bare facts of cases like these. This is, however, not so much the case for journalists engaging in meta-analysis, and much less so for the rest of us, especially those discussing rape in informally therapeutic environments.

I wish to suggest that, outside of discussions where jurisprudence and primary reporting of facts is relevant, “belief” and “knowledge” are less relevant than “trust” and consequences. I have more than one Facebook friend who has claimed to have been raped as a child and I trust them when they make these claims.

In fact, unless I’m provided with evidence to the contrary, that a given accusations is a lie or a fabricated memory, or unless I’m in a jury, I’m going to presume the truth of what they are saying. The presumption of innocence for the accused, in the context I’m talking about, is not of consequence, because the accused isn’t on trial, nor are they being excoriated by a populist media (or equivalent).

I’m opting, as much as I can, to withdraw from the language of “belief” and of “knowledge” in public discussions of the experiences of rape victims. If you’re not a juror, nor a frontline journalist (or equivalent), it’s not like the welfare of the Woody Allens of the world hinges on your believing them.

Conversely, it’s more likely that you’ll come into contact with someone who has been raped, who needs and deserves your moral support and trust.

***

Before I continue, I’ll point out that I don’t – nor should I - expect in discussions of rape that people who have been raped be as exacting about language as I choose to be. With the exception of the discussion of a few related issues that trigger my depression, I’m in a position to make these distinctions with relative ease.

I’m less forgiving of people who haven’t been sexually assaulted, or people who are purportedly professionals, or responsible community leaders, exercising less care with their language, or being uncharitable in interpreting the language of others. Aside from time and patience, nothing is lost by being thoughtful.

***

So, as I said, I’ve got a Facebook friend – Angie Jackson – who informed her friends that she was raped as a child, and unintentionally courting the sophistry of The Good Juror, in light of all the doubt being poured on Dylan Farrow, innocently asked by way of status update, if she herself was believed. Here’s some of what she copped as a result…

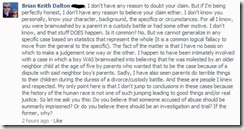

“Kids have made up stories of abuse. That is undeniable. Kids have also been brainwashed into believing they were abused by parents (and others) in a custody battle. This too is undeniable. These facts are the reason such claims are investigated and people are not simply put in jail without an investigation, evidence, and trial. I am inclined to neither believe nor doubt any claim based solely on the claim itself. My doubt or acceptance of the claim is based rather on the supporting evidence. Is that really so radical and/or wicked as to elicit such hostility?” – Brian Dalton.

For those not familiar with the name, Brian Dalton is the chief creative force behind the disastrously kitsch series of YouTube videos detailing the tribulations of his satirical “Mr Deity” character. I caught his talk on his experiences as an ex-Mormon at the Gala Dinner at the 2012 Global Atheist Convention in Melbourne, which I found much more interesting than his comedy or scepticism.

It needs pointing out, that despite the mention of “belief”, it was established emphatically prior to Dalton’s comment, that the discussion was not about establishing a guilty verdict, or locking anyone up, or “all those men who get away with rape”, or reaching for the pitchforks. It was at base, and was little more than being, about people’s online relationship with Angie, and that’s it.

All that Dalton’s observations achieved was to point out that it is logically possible for someone to lie, or for people to be brainwashed, but this doesn’t obligate anyone to suspend their trust in Angie. Moreover, these kinds of concerns weren’t even being denied to begin with – Dalton merely pointed out what everybody in attendance already knew.

Forget the courtroom. A setting more analogous to the conversation Dalton injected his opinion into would have you playing the role of a supporting friend or counsellor. Contrary to the Good Juror: as a matter of decision making, while they may be cautious, counsellors don’t suspend their belief in rape allegations.

Dalton may make a Good Juror, but what kind of friend would his red-herring-ridden hectoring make him to people who’ve been sexually assaulted without establishing the fact in court? This isn’t a purely emotive concern – the atheist community has a sizeable subset of people who have left religion owing to sexual abuse, and not all of them have had their day in court. Is Dalton going to talk down to them about the bleeding obvious as well?

Many people in our community can’t avoid making decisions relating to these matters, and a lecture on why people like Dalton don’t “believe or disbelieve” the sexual abuse claims of individuals doesn’t get this decision making done (more on that later).

Dalton continues….

“Angie, I don’t have any reason to doubt your claim. But if I’m being perfectly honest, I don’t have any reason to believe your claim either. I don’t know you personally, know your character, background, the specifics or circumstances. For all I know, you were brainwashed by a parent in a custody battle or had some other motive. I don’t know, and that stuff DOES happen. Is it common? No. But we cannot generalize in any specific case based on statistics that represent the whole (it is a common logical fallacy to move from the general to the specific). The fact of the matter is that I have no basis on which to make a judgement one way of the other. I happen to have been intimately involved with a case in which a bay WAS brainwashed into believing that he was molested by an older neighbor child at the age of five by parents who wanted that to be the case because of a dispute with said neighbor boy’s parents. Sadly, I have also seen parents do terrible things to their children during the duress of a divorce/custody battle. And these are people I knew and respected. My only point here is that I don’t jump to conclusions in these cases because the history of the human race is not one of such jumping leading to good things and/or real justice. So let me ask you this: Do you believe that someone accused of abuse should be summarily imprisoned? Or do you believe there should be an investigation and trial? If the former, why?” – Brian Dalton.

Again, keep in mind that it had already been pointed out that the discussion was not about sending people to jail, or custody battles, or about courts at all. The continued hectoring of people who claim to have been raped, with arguments like this, whether you believe their claims or suspend your belief, is more than fair invitation to criticism.

Yes, inferring from the general directly to the specific is a logical fallacy, but what if you make communicating like this with people who claim to have been raped a general policy? Probability comes into play again, and it is probable that if you keep it up, you’re going to be hectoring people who have been raped. Dalton gives no indication that he is singling Angie out for special treatment, so we can be reasonably safe in assuming that this is a general policy for him, even if not on the basis of his past form.

***

So if people aren’t talking about court battles, and being a Good Juror is beside the point, what is the point?

It’s not enough to simply make the distinction of “trusting” to denote something in a different category than “believing”, without actually having a bit more underlying the distinction. Without that, it’s closer to being a get-out-of-jail-card to be used in awkward situations, than anything else.

At base what I’m talking about when I mention “trust” (and it’s something that’s impossible to avoid) is decision-making, and Bayesian guesstimation. Verdicts, and the matter of believing/knowing them, are matters of hypothesis testing, which is something else.

Opting to give moral support to a friend who makes a rape allegation, may entail consideration of the merits of the accusation, but at base this is an exercise in decision making. Choosing to pick up their kids; make them meals because they’re too depressed to cook; give money to fund legal expenses, all because they claim to have been raped; these are decisions, not hypothesis tests.

The decisions are made on the balance of probability, weighted by the consequences of different choices – and it is not an appeal to consequences fallacy to do so, because again, we’re making choices, not testing hypotheses.

Of course, people (usually MRAs) will complain that one can make inferences about character from people’s decisions, and that this potentially threatens The Good Reputation ™ of the accused. Aside for there being no good reason to self-censor signs of support for someone making a rape allegation, it’s a sign of unchecked privilege when someone claims reputation must necessarily be treated with legalistic precision.

This is because in the first instance, it is literally impossible to consider all matters relevant to reputation in a purely legalistic (or para-legalistic) fashion – only those who can afford to force the point can, and even then not always. Further, it’s far more common than not in our culture for reputation to be managed via decision making; ‘will I employ so-and so?’, ‘do I want to hang out with this person?’, ‘which mechanic will I take my car to?’ – if you can envision these decisions being made without legalistic precision, then you’ve ceded my point.

As far as conventions and organisations in atheist circles go, there’s ‘do I invite this person who has been accused of rape to speak?’ and ‘do I want this person to assume this office?’ This is often the source of an underlying anxiety for public speakers, which in atheist/secular/humanist circles has flared up amongst brattish types in response to harassment policies and claims of sexual harassment.

But this is how reputation is normally addressed and it isn’t going to change any time soon, and to expect better is to expect special treatment. Of course, the usual suspects expect exactly this and as a result, in the atheist community, we have much wailing and gnashing of teeth over the prospective standings of atheist speakers and writers.

Strangely enough, nobody objecting to these ‘witch-hunts’ and ’purges’ by ‘Feminazis/Femistazis’ bother to consider the set of people whose reputation doesn’t allow them to speak at conventions, but who could, and who could do it well if not better than most. Such potential good speakers didn’t earn their lack-lustre reputations, nor did they get such reputations from nowhere, but they don’t deserve their lesser standing any more than at base, the more fortunate deserve theirs.

(And don’t get me started on the contempt towards volunteers, inherent in this sense of entitlement).

Attempts at the preservation of special treatment seem to motivate a lot of The Good Juror pose (and a good deal of nepotism to boot).

***

While it may also have the potential effect of partitioning public opinion away from a jury, my primary intention is for the trust/belief distinction, and any demarcation that goes with it, to circumvent the involvement of The Good Juror in discussions and decision making where it would be ill-placed. There would of course be push-back from the usual suspects and enablers (even if they didn’t push back against… everything).

Let’s be blunt. Often The Good Juror should know full well that the context into which they are deploying their lectures doesn’t and needn’t involve hypothesis testing to a judicial standard (or hypothesis testing at all). For what it’s worth, I don’t trust that Brian Dalton is oblivious to this at all.

Aside from the blunt-instrument effect you’d expect from Dalton’s lecturing in an irrelevant context about concerns of jurisprudence, there’s a second, more insidious aspect to The Good Juror Pose. Specifically, it hides the process of decision-making that The Good Juror must be undertaking on some other level.

In Dalton’s case, it could be ‘will I choose to make back-handed jokes about rape allegations, or will I opt not to be dismissive’, or ‘will I continue to work side by side with my friend Shermer, or wait until this blows over?’… If you’re cynical about Dalton, you may suspect considerations along the lines of ‘how can I exploit the stress that Michael Shermer is under to my own advantage?’

Again, we are talking decisions, not hypothesis tests, and unless Brian Dalton has no executive function at all, something resembling these considerations must be occurring in addition to his thoughts about “belief/disbelief”. This is Dalton the decision maker – the Good Juror Pose is just that: a pose; a mask.

When you recognise this, you’ve reached the root question relevant to all such scenarios; ‘by what criteria should I make decisions on how to interact with people who say they’ve been raped?’

People will differ, of course, on these criteria. Deontologists, virtue theorists and utilitarians could argue at length. The libertarians who peddle Ayn Rand (who don’t really belong in a category of philosophers), and the people who suck up to them, can be expected to engage in self-serving rationalisations – this is at base, why in these matters, I don’t trust Brian Dalton, or Michael Shermer, or Penn Jillette, or DJ Grothe, etc..

(Well, that and previously documented acts of bullshit artistry by the libertarian primaries).

What needs to be asked, when The Good Juror interlopes outside their remit, is ‘why the pose, and what criteria are you are using to measure your behaviour?’ ‘Are those criteria self-serving or altruistic?’

(One wonders what Brian Dalton’s criteria actually are, or if he’s actually reflected upon them.)

***

The only concession arising out of this, that needs to be made in the opposite direction, is to recognise that “belief” in claims being made, given certain circumstances (being on a jury, journalism reporting on factual claims, and where vigilantism is a probable risk), needs to show due scepticism. That is to say, that sceptical, rigorous discussions of truth claims, even painful truths, have their place where the presumption of truth shouldn’t occur.

However, not all forums for rape survivors where claims are discussed, even where the claims may in fact be unresolved and genuinely contentious, entail prejudicing a jury, producing poor journalism, or setting the torches and pitchforks in motion. And these forums, these informal therapeutic environments, are very much needed in atheist and humanist circles.

What is needed, I think, where possible, is clearer demarcation of these zones in the same vein as “trigger warnings” – something that should be facilitated by those in a position to do so; organizational leaders, professional bloggers and public speakers, may be in a position to help prevent the damage that can occur when these domains leak into each other.

And of course, to varying extents, we can self-regulate, and pay attention to what environment we’re speaking in. Hopefully the Brian Daltons of the scene can heed the signposts a little better in future as well.

Bruce Everett

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)