Michael Nugent and Leah Libresco talk about the latter’s conversion from atheism to Catholicism, and what moral realism has to do with it.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3GOKh5TXjUM

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

Michael Nugent and Leah Libresco talk about the latter’s conversion from atheism to Catholicism, and what moral realism has to do with it.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3GOKh5TXjUM

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

More nostalgia – May 21 2012 when the bishops announced their lawsuit against the administration. Catholic News Service was there, slavering.

The Archdiocese of New York, headed by Cardinal Timothy Dolan, the Archdiocese of Washington, D.C., headed by Cardinal Donald Wuerl, the University of Notre Dame, and 40 other Catholic dioceses and organizations around the country announced on Monday that they are suing the Obama administration for violating their freedom of religion, which is guaranteed by the First Amendment to the Constitution.

The dioceses and organizations, in different combinations, are filing 12 different lawsuits filed in federal courts around the country.

The Archdiocese of Washington, D.C. has established a special website–preservereligiousfreedom.org–to explain its lawsuit and present news and developments concerning it.

“This lawsuit is about an unprecedented attack by the federal government on one of America’s most cherished freedoms: the freedom to practice one’s religion without government interference,” the archdiocese says on the website. “It is not about whether people have access to certain services; it is about whether the government may force religious institutions and individuals to facilitate and fund services which violate their religious beliefs.”

The suits filed by the Catholic organizations focus on the regulation that Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius announced last August and finalized in January that requires virtually all health-care plans in the United States to cover sterilizations and all Food and Drug Administration-approved contraceptives, including those that can cause abortions.

The Catholic Church teaches that sterilization, artificial contraception and abortion are morally wrong and that Catholics should not be involved in them. Thus, the regulation would require faithful Catholics and Catholic organizations to act against their consciences and violate the teachings of their faith.

The Catholic Church teaches that contraception is morally wrong but it doesn’t teach that priests’ raping children is morally wrong.

The Catholic church is morally garbage; rotten stinking putrescent slime-green garbage.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

The US Conference of Catholic Bishops – which aspires to tell the secular government what to do, and has much success in doing just that – has a campaign for religious libery, by which of course it means the USCCB’s liberty to tell everyone else what to do. It’s pushing for a “Health care conscience rights act” – and we all know what they mean by that. They want Congress to make it a law that they have a “right” to refuse to do their jobs if that involves medical treatments they choose to have “religious” objections to. They have a fact sheet on the subject.

The right of religious liberty, the First Freedom

guaranteed by our Constitution, includes a right to

provide and receive health care without being required to

violate our most fundamental beliefs.

No it does not. No no no. That is not a right. There is no “right” to practice medicine while refusing to do part of the job because of your made-up religious scruples. The right that matters here is the right to get medical treatment on equal terms with everyone else. There’s no “right” to refuse to serve people of color or LGBT people or women, for example. There’s no “right” to refuse to perform abortions or dispense contraceptives.

Especially since

1973, when abortion became legal nationwide, federal

lawmakers have worked in a bipartisan way to ensure that

Americans can fully participate in our health care system

without being forced to take part in abortion or other

procedures that violate their conscience.

Then they need to stop doing that, and do the other thing. They need to ensure that all patients are served and on an equal footing with all others. Period.

But the need to improve current laws is clear, because the

right of conscience is still under attack:

· Under the new health care reform law, the federal

government is demanding that almost all health plans

fully cover female sterilization and a wide range of

drugs and devices to prevent pregnancy, including

those that can cause an early abortion. Even

individuals and organizations with a religious

objection to abortion, sterilization or other

procedures are forced to take part.

· A Catholic agency that for years had provided

excellent service lost its federal grant to serve the

victims of human trafficking, because it could not, in

conscience, comply with a new requirement to

facilitate abortions and other morally objectionable

procedures for its clients.

· Dedicated health care professionals, especially nurses,

still face pressure to assist in abortions under threat of

losing their jobs or their eligibility for training

programs.· In some states, government officials are seeking to

force even Catholic hospitals to allow abortions or

provide abortion coverage in order to continue or

expand their ministry.

This is why members of Congress of both parties are

sponsoring the Health Care Conscience Rights Act (H.R.

940, S. 1204). The Act would improve federal law in

three ways:

1. Correcting loopholes and other deficiencies in the

major federal law preventing governmental

discrimination against health care providers that do

not help provide or pay for abortions.

2. Inserting a conscience clause into the health care

reform law, so its mandates for particular “benefits”

in private health plans will not be used to force

insurers, employers and individuals to violate their

consciences or give up their health insurance.

3. Adding a “private right of action” to existing federal

conscience laws, so those whose consciences are

being violated can go to court to defend their rights.

(Current enforcement is chiefly at the discretion of

the Department of Health and Human Services,

which is itself sponsoring some attacks on

conscience rights.)

All House and Senate members should be urged to

support and co-sponsor the Health Care Conscience

Rights Act, so our First Freedom can regain its proper

place as a fundamental right protected in our health care

system.

They have to be stopped.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

Let’s have a blast from the past: Katha Pollitt in the Nation in December 2011.

Who matters more to President Obama, 271 Catholic bishops or millions upon millions of sexually active Catholic women who have used (or—gasp!—are using right this minute) birth control methods those bishops disapprove of? Who does Obama think the church is—the people in the pews or the men with the money and power? We’re about to find out. Some day soon the president will decide whether to yield to the US Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), which has lobbied fiercely for a broad religious exemption from new federal regulations requiring health insurance to cover birth control with no co-pays—one of the more popular elements of Obama’s healthcare reform package. Talk about the 1 percent and the 99 percent.

There’s already an exemption in the law for religious employers, defined as those whose primary purpose is the “inculcation of religious values,” who mostly serve and employ people of that faith, and qualify as churches or “integrated auxiliaries” under the tax code. That would be, say, a diocesan office or a convent or, for that matter, a synagogue, mosque or megachurch. Even this exemption seems unfair to me—why should a bishop be able to deprive his secretary and housekeeper of medical services? The exemption is based on the notion that people shouldn’t have to violate their religious consciences, but what makes his conscience more valuable than theirs? I would argue that it is less valuable—he’s not the one who risks getting pregnant.

What indeed? Perhaps it’s just that Obama was and is cowed by the institution and the guys who are at the top of that institution. Or perhaps it’s not that he’s cowed by them, but that he’s impressed by them. Perhaps he takes them at their own valuation.

The exemption becomes truly outrageous, though, if it is broadened, as the bishops want, to include Catholic hospitals, schools, colleges and social service organizations like Catholic Charities. These workplaces employ millions; and let’s not forget their dependents and the roughly 900,000 students enrolled at Catholic colleges. Now we’re talking about lots of people who aren’t Catholics, who serve non-Catholics and whose workplace may have only a tenuous connection to the institutional church. The Jewish social worker, the Baptist nurse, the security guard who hasn’t seen the inside of a church in decades—all these people, and their spouses and other dependents, will have to pay out of pocket, even as most Americans applaud the advent of vastly broadened access to essentially free contraception. It’s not a small amount of money at stake, either—the pill can cost $50 a month. The IUD, wider use of which would do much to help lower our high unintended pregnancy rate, lasts for many years but costs $800 to $1,000 up front. How is it fair to make millions of women live under old rules that the rest of society is abandoning precisely because they are injurious to health and pocketbook? Is there a social value in a woman’s having to skip her pills because she’s short $50? If it was any medication other than birth control—sorry, the Pope thinks you should control your cholesterol through prayer and fasting; no statins for you!—more people would be up in arms.

In the event, Obama gave them the first part of the exemption, and SCOTUS gave them the rest. Their rigid sex-hating anti-woman religious views were allowed to trump the views of people who need the coverage and people who think they should have the coverage. It’s a stupidly hierarchical move, given that it’s well known that most Catholics totally ignore the Vatican prohibition on contraception. Why does the fanatical minority get an exemption that harms the more liberal, reasonable majority?

In the bishops’ topsy-turvy world, religious liberty means the state must enable them to force their medieval views on others. Thus it was “anti-Catholic” for HHS not to renew a 2006 contract with the bishops’ refugee-services office to help victims of human trafficking—never mind that the office denied these women, often victims of rape and forced prostitution, birth control and emergency contraception. In what world do people have the right to be hired to not provide services? You might as well say it’s bigoted to deny the Jehovah’s Witnesses a contract to run a blood bank. You can expect more of this self-serving nonlogic from the USCCB’s newly beefed-up Committee on Religious Liberty, which plans to fight for broader religious exemptions in certain areas, such as the “right” to use federal funds to discriminate against gays in adoption and foster-care placements.

Theocrats are flexing their muscles.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

The Iona Institute has a new self-promotion video.

It tells us what it believes. It believes every child, once conceived, has the right to be born.

It believes the separation of church and state should not mean the separation of religion and the public square.

It believes all people have the right to do what bishops tell them to do.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

So now I’m trying to work my way back through the history of RFRA, to try to figure out why it had so much support, from the left as well as the right.

The ACLU has a relevant article on its site…but it has no date, which is very unhelpful. But for what it’s worth…

Religious freedom is a fundamental human right that is guaranteed by the First Amendment’s Free Exercise and Establishment clauses.[1] It encompasses not only the right to believe (or not to believe), but also the right to express and to manifest religious beliefs. These rights are fundamental and should not be subject to political process and majority votes. Thus the ACLU, along with almost every religious and civil rights group in America that has taken a position on the subject, rejects the Supreme Court’s notorious decision of Employment Division v. Smith. In Smith, Justice Scalia wrote that the accommodation of religion should be left “to the political process” where government officials and political majorities may abridge the rights of free exercise of religion.[2]

That’s just way too broad – that “but also the right to express and to manifest religious beliefs.” It’s just not true that there’s a sweeping general right to express and to manifest religious beliefs no matter what – it’s a conditional right that can be trumped by more basic rights. Some – indeed many – religious beliefs justify or mandate murder, torture, inequality before the law, subordination of women, genocide, you name it. In the US religious beliefs mandate the forced marriage of underage girls to men decades older; they mandate refusal to get medical treatment for children with treatable diseases; they mandate female subordination; they mandate refusal to vaccinate children.

So, weird city, on this one I agree with Scalia and disagree with the ACLU – but a lot of people are in that position, especially now in the wake of Hobby Lobby. Scalia himself has notoriously shifted.

The note under [2]:

[2] Employment Division v. Smith, 494 U.S. 872, 890 (1990). The majority opinion was written by Justice Scalia and joined by Chief Justice Rehnquist and by justices White, Stevens, and Kennedy. The Court held that a neutral law of general applicability may constitutionally result in incidental restrictions on free exercise where there was no contention that the government intended to target religious activity with the law. (The ACLU filed an amicus brief before the Court arguing that the free-exercise right should prevail.) The national opposition to the Smith case and its reasoning was overwhelming. The ACLU joined with a broad coalition of religious and civil liberties groups, including People for the American Way, the National Association of Evangelicals, the Southern Baptists’ Ethics Religious Liberty Commission, and by many other groups to urge Congress to reinstitute the rule that religious freedom could be constrained solely if the government had a “compelling interest” in doing so. The Congress agreed overwhelmingly with the ACLU’s position (that was rejected by Justices Scalia, Rehnquist, White, Stevens and Kennedy), and adopted the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 unanimously in the House and by a vote of 97-3 in the Senate.

Bad move.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

You know how team sports is the source of all virtue? Not so much.

Conor Friedersdorf talking to New York Times religion reporter Mark Oppenheimer

I was particularly intrigued by your article about Christians who play football–how they reconcile their faith, with its emphasis on humility and turning the other cheek, with their sport, where hitting opponents as hard as one can, to the point of trying to hurt them, is the norm. How was that article received in our football loving culture? Did any of the feedback help you to better understand the phenomenon?

That’s actually an article where my initial suspicions were only confirmed and amplified by my reporting. Football lovers like to think that team sports, and football in particular, promote virtue for those who play them. It’s clear the opposite is true. The research shows that participation in high-level athletics makes one less moral, more interested just in winning. And my interviews with Christian coaches were horrifying: they all justify to themselves all kinds of violence on the field, as well as dishonesty. Take an issue like lying to a referee: “Yes, I made that catch! I didn’t drop the ball!” Now, you’d think a “Christian” player would put some premium on telling the truth. But they all rationalize lying, in part because everyone does it. As if God’s rules can take a back seat to the custom of the sport.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

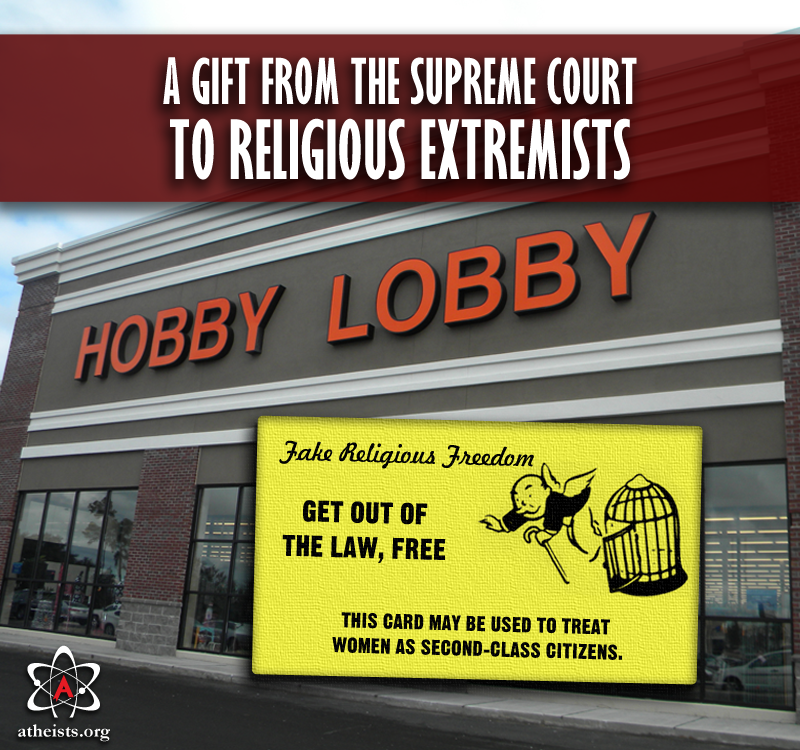

From the White House press briefing yesterday; the first question was about the Hobby Lobby ruling.

The Supreme Court ruled today that some bosses can now withhold contraceptive care from their employees’ health coverage based on their own religious views that their employees may not even share. President Obama believes that women should make personal health care decisions for themselves rather than their bosses deciding for them.

Today’s decision jeopardizes the health of women who are employed by these companies. As millions of women know firsthand, contraception is often vital to their health and wellbeing. That’s why the Affordable Care Act ensures that women have coverage for contraceptive care, along with other preventative care like vaccines and cancer screenings.

We will work with Congress to make sure that any women affected by this decision will still have the same coverage of vital health services as everyone else.

President Obama believes strongly in the freedom of religion. That’s why we’ve taken steps to ensure that no religious institution will have to pay or provide for contraceptive coverage. We’ve also made accommodations for non-profit religious organizations that object to contraception on religious grounds. But we believe that the owners of for-profit companies should not be allowed to assert their personal religious views to deny their employees federally mandated benefits.

Now, we’ll of course respect the Supreme Court ruling and we’ll continue to look for ways to improve Americans’ health by helping women have more, not less, say over the personal health decisions that affect them and their families.

That crap about the freedom of religion is crap. Religious institutions and non-profit religious organizations shouldn’t get special exemptions from laws that apply to everyone else – and that includes employment laws; religious institutions should not be exempt from equal employment laws; yes even as applied to the clergy. As Amanda Kneif pointed out yesterday, Obama made a big damn mistake carving out those special exemptions. One Law For All, people.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

The Washington Post gives its (as it were corporate) view of the Hobby Lobby ruling and what it implies.

When business owners enter the public marketplace, they should expect to follow laws with which they might disagree, on religious or other grounds. This is particularly true when they form corporations, to which the government offers unique benefits unavailable to individuals.

The Supreme Court weakened that principle Monday. Congress should revitalize it.

That’s one good way of putting it. The public marketplace, like most public places, is fundamentally secular. Gods don’t need commerce or trade, because they don’t need goods and services, because they don’t need anything, because they’re gods. We need them, we humans, who live here in the secular world. That’s one reason we need secular laws and secular agreements and contracts and habits.

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act muddied these waters.

If this is the sort of balancing that the Supreme Court will conduct, Congress should change the law. The Constitution generally does not require religious exceptions to generally applicable laws. The ruling relied on the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, a statute that does not mention corporations and that lawmakers could easily narrow. They should not only guarantee contraception coverage but also repair the federal government’s ability to provide for wholly legitimate common goods such as public health and marketplace regulation.

Catholic bishops already interfere with a hefty percentage of US health care via all the Catholic-owned hospitals and networks of hospitals. Bishops and church doctrine should have no role in public health at all.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

Originally a comment by the philosophical primate on The American Humanist Association comments.

I wish people would quit talking about this case in terms of “corporate rights” and “corporate personhood” and the like. That’s a red herring. The decision prominently mentions the legal relevance of the fact that Hobby Lobby (and the other plaintiffs) are “closely held corporations” — that is, owned by a small number of shareholders rather than being publicly traded companies — and the decision was rationalized (I won’t dignify it with the word “justified”) on the basis that it protects the religious liberty OF THOSE INDIVIDUAL PERSONS. Yes, those persons own a company, but the rights at stake were the rights of the owners as persons, and religious rights were not in any way imputed to any corporation.

Here’s how the Hobby Lobby case reasoning works: The owners of Hobby Lobby claim, based on the language of the (misleadingly named, unnecessary, and poorly written) Religious Freedom Restoration Act, that the ACA’s requirement that all employers (above a certain size) pay some of the costs of comprehensive health coverage “substantially burdens” their religious liberty. How, exactly? Because comprehensive health insurance coverage includes contraception, and they don’t like contraception — because religion.

Now surely the owners of Hobby Lobby et al have a right to that religious opinion as individual people, and I’ll readily grant that the government would be unduly burdening their religious liberty if it were forcing them to use or purchase contraception. But it’s not quite so obvious that there is any encroachment on religious liberty in forcing them to pay for comprehensive health coverage for their employees. In fact, it’s the opposite of obvious. It’s downright obscure why anyone would think so.

How is paying for their employees’ insurance coverage — which employees may or may not use to acquire contraception — any different from paying their employees’ salaries, which employees also may or may not use to acquire contraception (or any of a number of other things that their employers might find disagreeable for religious reasons)? Yes, there is a purely practical difference that contraception can be expensive, but surely there is no difference in principle. To claim that a burden has been imposed on one’s liberty logically requires that one actually has some genuine right at stake — and employers have no legal or moral right to restrict, coerce, or influence in any way the private medical decisions of their employees any more than they have a right to tell their employees how to spend their paychecks. The claim that the employers in this case have any religious liberty that is being burdened in any way, “substantial” or not, is flatly ludicrous. (But, I repeat, that claim is not based on any notion that corporations as legal persons now have religious freedom to go along with their (mistakenly, foolishly, unjustifiably granted) freedom of speech.)

If anything, the religious liberty of *employees* is very substantially burdened by this decision, because it allows employers to arbitrarily limit employees’ access to health care and thereby impose their own private religious convictions on employees who may not (and probably do not) share them. But the primary burden here is on employees’ right to equality before the law: All people employed at companies above a certain size have a right to an employer-subsidized comprehensive insurance plan under the ACA — except now they don’t, if they have the misfortune of being employed by a privately-owned company whose owners claim they have a religious aversion to some perfectly ordinary health care option which comprehensive insurance plans are required to provide by law. This result is discriminatory on the face of it, even without the additional discrimination that MEN’S health care never seems to be an issue for anyone’s religious convictions.

For my part, I’m convinced that any time religious liberty clashes with equality before the law, the latter is a more fundamental moral and constitutional principle that ought to prevail. (Exceptions welcome, but I can’t think of any. And this is really why I think the RFRA is constitutionally unsound law, because it subordinates other constitutionally-guaranteed liberties to religious liberty.) But never mind that, because there is no plausible argument to be made that the comprehensive insurance coverage requirement of the ACA (which includes contraception, simply because it IS basic health care) imposes a “substantial burden” on the religious liberty of employers: Employers simply do not have any right — based in religious liberty or any other constitutional or legal principle — to make health care decisions (or any other personal or financial decisions) for their employees, so that right cannot be encroached on by the ACA or any other law.

So why did the five-MAN majority of the SCOTUS offer downright silly legal rationalizations in support of the rationally and legally insupportable claim that employers have some religious liberty that is substantially burdened by being required to provide comprehensive insurance coverage (including icky, icky contraceptive care) to employees? Because five white Catholic men are ideologically predisposed to dislike women in general and contraception in particular. And because those same men are willing tools of the plutocracy who always show a clear preference for expanding the power of employers over the protecting the rights of employees.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

Haha don’t worry. The pope may present himself as some kind of lovable guy who just happened to bumble his kindly way up the hierarchy of an evil institution, but don’t worry, he’s still a patronizing clueless eyes-closed asshole about women. Whew, what a relief, right? He’s normal, and he won’t be giving all the expensive real estate away to some poor people.

The pope said women were “the most beautiful thing God has made”. And he added: “Theology cannot be done without this feminine touch.”

He agreed not enough was said about women and promised that steps were being taken to remedy the situation.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

Soraya has commentary at Time magazine.

In the practice of many religions, girls’ and women’s relationship to the divine are mediated, in strictly binary terms, by men: their speech, their ways of being and their judgments. Women’s behavior, especially sexual, is policed in ways that consolidate male power. It is impossible to be, in this particular case, a conservative Christian, without accepting and perpetuating the subordination of women to male rule. It is also blatant in “official” Catholicism, Mormonism, Evangelical Protestantism, Orthodox Judaism and Islam.

The fundamental psychology of these ideas, of religious male governance, does not exist in a silo, isolated from family structures, public life or political organization.

It certainly does not exist separately from our Supreme Court. Antonin Scalia, for example, makes no bones about his conscientious commitment to conservative Catholic ideals in his personal life and the seriousness of their impact on his work as a judge. There are many Catholics who reject these views, but he is not among them. These beliefs include those having to do with non-procreational sex, women’s roles, reproduction, sexuality, birth control and abortion. The fact that Scalia may be brilliant, and may have convinced himself that his opinions are a matter of reason and not faith, is irrelevant.

What is not irrelevant is that we are supposed to hold in abeyance any substantive concerns about the role that these beliefs, and their expression in our law, play in the distribution of justice and rights. They are centrally and critically important to women’s freedom, and we ignore this fact at our continued peril.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

The legal staff at American Atheists is doing a live ask questions thing about the Hobby Lobby ruling in 50 minutes from now, 7 pm Eastern time, 4 my time, midnight UK time.

Update: here is the video link.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W25-WjDLuKY

I know what I want to ask. On p 3 of the Hobby Lobby ruling we are told that the purpose of granting rights to corporations is to protect the rights of people associated with the corporation, including shareholders, officers and employees. What’s to prevent a group of shareholders and/or employees from counter-suing to seek protection for *their* rights?

Why do the putative rights of the owners of Hobby Lobby get to trump the rights of all those other people? There’s bound to be a cacophony of religious beliefs in play, including zero religious beliefs; what can be the rationale for protecting some at the expense of all the others?

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

A survivor of one of the Magdalene laundries a Canadian home for single mothers in the 1970s left a comment in a Facebook group for such survivors yesterday. It froze my blood, and I asked the author if I could post it on my blog, with or without her name. She said yes just now, with no name (so I’m not linking, either).

I suppose this is one of those times when I should include a trigger warning. This is a horrible story.

In the home that I was in, me and another unwed mother (both of us were 8 months gone) were forced to deliver a dead deformed baby of another of the mothers there. This was done to punish all of us. The hospital had sent this poor girl back to the home to deliver the dead baby. The staff locked themselves in the office and refused to help. This poor girl should have been in hospital but as the hospital knew her baby was dead inside of her (it appears that it was Anencephaly), they didn’t care. She was 7 months gone. I sometimes still have nightmares about that. The office staff didn’t even come out when the ambulance arrived (not sure who called them but glad someone did).

1 Corinthians 13, anyone? Caritas?

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

“The Supreme Court has placed the religious views of corporate shareholders over the legitimate health care concerns of employees,” said Roy Speckhardt, executive director of the American Humanist Association. “This isn’t religious liberty—it’s religious intrusion that will negatively affect many hard-working Americans.”

By privileging the religious views of corporate owners, the ruling places a substantial burden on women who wish to obtain birth control methods, such as the IUD or morning after pill, the costs of which can be as high as $1,000 annually. The ruling may also spur other for-profit corporations to deny employees access to certain medical procedures, based on their owners’ personal creeds.

“The Supreme Court is endangering the health care of many Americans based on the fictitious idea that a corporation has religious convictions,” said David Niose, legal director of the American Humanist Association’s Appignani Humanist Legal Center. “By expanding the rights of corporations, this court is in fact contracting the rights of hard-working Americans who expect full health care coverage as required by law. ”

In January, the American Humanist Association, with other secular and humanist organizations, signed on to an amicus curiae brief in support of the government that argued a ruling in favor of Hobby Lobby and Conestoga Woods would violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

Via the always useful Cornell Legal Information Institute.

(a) In general

Government shall not substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion even if the burden results from a rule of general applicability, except as provided in subsection (b) of this section.

(b) Exception

Government may substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion only if it demonstrates that application of the burden to the person—

(1) is in furtherance of a compelling governmental interest; and

(2) is the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling governmental interest.(c) Judicial relief

A person whose religious exercise has been burdened in violation of this section may assert that violation as a claim or defense in a judicial proceeding and obtain appropriate relief against a government. Standing to assert a claim or defense under this section shall be governed by the general rules of standing under article III of the Constitution.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)