MSNBC reports on the Men’s Rights conference held in Michigan yesterday.

“I call it the evil empire,” Erin Pizzey, the British founder of one of the first domestic violence shelters and a staunch anti-feminist, said Friday, borrowing Ronald Reagan’s description of the Soviet Union. “We need to go after them. We cannot allow this to continue. And if we don’t stop it, I don’t see a future for marriage, for love, or for anything.”

Yup. That totally makes sense. Feminism will mean the end for marriage, and love, and everything. Once it has done it’s work, there will be no future for anything. It will be like before the Big Bang.

There are real issues for men, obviously, most or all of them issues that feminists have been pointing out for decades. But…

But those issues got short shrift from most of the speakers on the first full day of the conference Friday, hosted by A Voice For Men, an online hub for men’s rights activists founded by Paul Elam. What animated most of the speakers at the conference was feminism and how it needed to be defeated.

Although generally understood as an ideology of equal rights for women, at the conference such feminists were called “equity feminists,” discussed the way Democrats might refer to “sane conservatives” or Republicans to “good liberals.” In other words, a largely fictional exception whose purpose is merely to define the whole as extreme. Feminists, for many of the speakers, were the enemy.

Heh. Take that, Twitter anti-feminists. The “equity feminism” bullshit isn’t fooling anyone, despite Sommers’s best efforts.

Mike Buchanan, a British men’s activist, warned that feminism was the ideology of “female supremacists, driven by misandry, the hatred of men and boys.” For 30 years, Buchanan said, “feminists have worked through the state to attack many of the pillars of civilized society,” and become “the defining ideology, of the political establishment.”

At the conference, feminism was responsible for turning wives against their husbands, bleeding them dry in divorce proceedings and separating them from their children, levying false accusations of rape and abuse against good men, or creating an ever-present culture of hatred where men are vilified.

Though men’s rights activists who hosted the conference often say sexual assault against men isn’t taken seriously, the audience laughed when speaker Fred Jones mentioned his fears about his son being raped after being arrested in New Orleans.

“He’s kinda small and kinda cute, good looking, you know what I mean?” Jones said. “You know what they do with –” Jones cut himself off. But the audience laughed.

Because prison rape is so hilarious. Ok…

Barbara Kay, a columnist for Canada’s National Post, argued that Santa Barbara shooter Elliott Rodger couldn’t have been driven by hatred of women because “he hated women because they rejected him sexually, but he also hated men because they had access to women.”

Rape on college campuses, she added, was a myth perpetrated by man-haters, and the concept of rape culture, how society can tacitly approve of or rationalize sexual assault, was “baseless moral panic.”

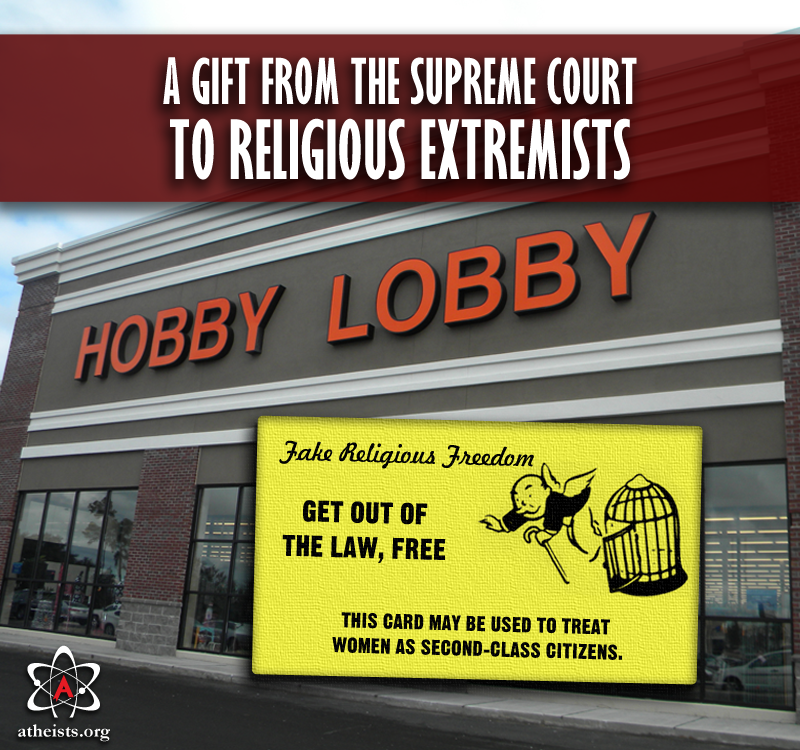

“The vast majority of female students allegedly raped on campus are actually voicing buyer’s remorse from alcohol-fueled promiscuous behavior involving murky lines of consent on both sides,” she said, drawing chuckles from the audience. “It’s true. It’s their get-out-of-guilt-free card, you know like Monopoly.” The chuckles turned to guffaws.

Hawhawhaw. Echoes of “distasteful locker room banter” and all the rest of the phrase book.

Dr. Tara Palmatier, a men’s rights activist who advertises herself as a “shrink for men,” explained that “feminism has evolved from the radical notion that women are people, to the radical notion that women are superior.”

…

Most of the speakers on the first full day of the conference were women, a fact Palmatier noted proudly. ”I am the third presenter to speak at the first annual international men’s human rights conference, and that would be the third woman presenter,” Palmatier said to applause. “My aren’t we an interesting group of misogynists. I hate to tell you guys, but I think we might be doing it wrong.”

I guess she’s never heard of Phyllis Schlafly, or even Michelle Duggar.

(This is a syndicated post. Read the original at FreeThoughtBlogs.)