Helen Lewis has a brilliant piece at the New Statesman about the attempt to no-platform Germaine Greer. Read every word.

It’s interesting that it is Greer’s views on gender that are the flashpoint, because she has been flat wrong about many things in her career – FGM, for example, which she has defended given its “cultural” element – without anything like the same backlash. Put simply, trans issues are the new dividing line for progressive activism; the way for younger activists to kick against their foremothers in the feminist movement.

And by god they do, with loathing and contempt.

Think about that for a second. Young feminist women – not all, obviously, but depressingly many – loathe and scorn old feminist women.

Well what does that say about the prospects for feminism? Feminism isn’t going to work if it applies only to young women, you know. If even feminist women hate old feminist women, then what hope is there that misogyny will ever fade away? If misogyny is that available and that pervasive and that irresistible…what hope is there?

I’m not sure there is much.

With gay marriage now legal in America, there is also the sense among online social justice communities that trans rights are “the new civil rights frontier” (as Time magazine wrote next to a photo of Orange is the New Black star Laverne Cox). Social media has acted like an accelerant on this fire: sites like Buzzfeed and Huffington Post’s LGBT section offer uplifting tales of transgender children’s achievements and famous adults coming out, alternating with occasional three-minute hates for “TERFs” (trans exclusionary radical feminists), a group who are said to be inciting violence against trans women by refusing to accept them as women. Sharing such articles has become a badge of progressive correctness. The word “TERF” is sprayed around like confetti, with very little understanding of what it means. I’ve been called a TERF, even though I think trans women are women and absolutely have a place in feminism. I think it’s become a politer way of saying “witch”.

And what is a “witch”? An evil old woman that we have a license to hate. We see her plastered against utility poles and trees everywhere at this time of year, having ridden her broomstick into one and crashed. All women are future old women, and we all hate old women, so how can we agree with feminism? We all reserve the right to hate women, dammit.

Trans activists, tired of being treated as objects of curiousity, fear or pity by outsiders, have decided to seize control of the discourse and develop their own ways of talking about how they feel. This is understandable, but it also means that everyone is constantly making mistakes. This would be OK – in everyday life, people slip up and get corrected, and the world keeps turning – but because it’s happening in the crucible of social media, where women’s opinions carry a higher cost, censure for those mistakes is distributed unfairly. There are phrases that a man could say – “female socialisation” springs to mind – with no comeback, but would be read as Deep TERF Code coming from a feminist’s mouth. I’ve lost count of the number of times that male friends have expressed surprise that their normally quiet, polite Twitter experience suddenly turns into a hornet’s nest if they chat with me about a controversial divide in feminism.

It’s not men who get demonized and hounded out, it’s women. It wasn’t two men that Improbable Joe “warned” me about on Twitter DM, it was two women – Helen Lewis being one of them. There are no outcries or “warnings” about TEMRAs – as far as I know TEMRA isn’t even a thing.

Even trans people who do not have the “correct” opinions feel worried about broaching the subject; I know a group of “gender critical” trans women who are castigated regularly as “TERF tokens” and “Uncle Toms”. (Putting paid to the flatulent piety so often circulated on social media: “Why don’t you just listen to trans people?” Because it turns out, O Wise One, that minority groups are not homogenous.)

Ok so it has to be “Why don’t you just listen to the right trans people?”

In my Pollyanna-ish way, I hope that all of these questions can be resolved with respectful negotiation; but there will have to be compromises between competing interests. It’s not – as many people on Twitter seem to believe – as simple as identifying the group you feel is most fashionably oppressed and sprinting to shout: “Solidarity!” And God save us from all the progressive men who will never face the sharp end of such questions – who have never had to think about rape shelter policy, for example – using this issue to show how right-on they are. Come on, feminists, they chirrup without self-awareness. Stop being so uptight!

Be like us: not talking over the marginalized!

But here is a list of things which can get you called a TERF, if you are a woman with a public profile: a) believing that biological sex is different from gender, ie that the penis is a male sex organ, even when attached to someone who identifies as a woman; b) believing that being raised as a boy gives you a different experience of life to anyone raised as a girl; c) believing that you need to transition using surgery or hormones to be trans (a recent Buzzfeed piece was headlined “This Trans Women Kept Her Beard And Couldn’t Be Happier”) d) believing that someone who transitions at 45 has not “always been female”.

I’d argue that those positions are far removed from the hateful, discriminatory behaviour and speech which most of us would accept is transphobic. And it is entirely possible that some or all of them will seem completely outdated in 50 years as our ideas about sex and gender move on. But they don’t seem to me to be in themselves vile or beyond the pale.

…

From the trans perspective, I can understand the feelings that the gains the movement has recently made are both recent and fragile, and the desire to set the terms of the debate after so long being treated as objects of pity or ridicule. After all, the challenges of transition are a daily task for many people, not a theoretical debate. But the subject has become part of a society-wide conversation; to move on, it must be something that ordinary people, outside the charmed circle who know that trans no longer takes an asterisk, can have an opinion on.

It also needs to be something that’s not a pretext for attacking feminist women.

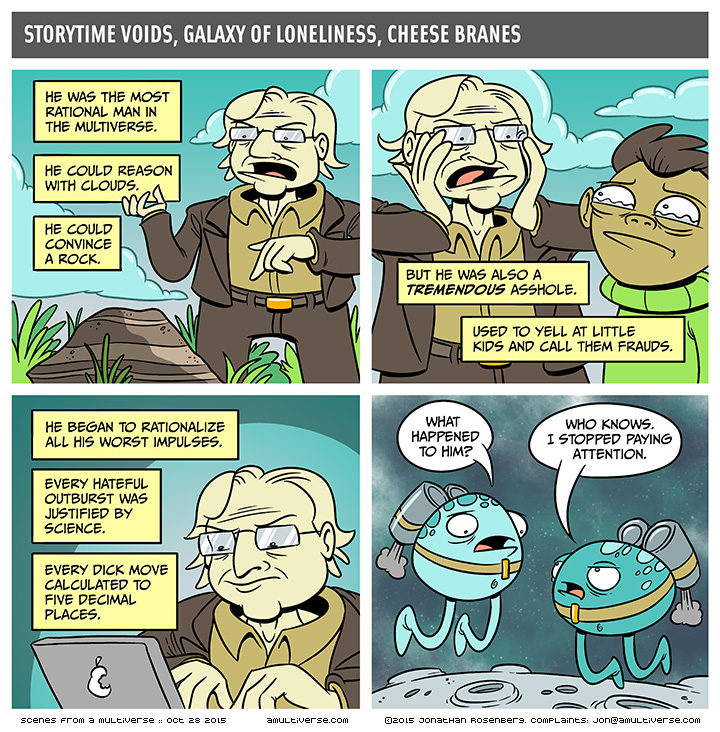

This battle against Germaine Greer is driven, at least in part, by sexism. After all, the world is full of academics with bad opinions, happily going about their business. Richard Dawkins, for example, is obsessed with proving that a teenage Muslim American boy suspended for bringing a clock to school should not be an object of pity and is instead a cunning hoaxer. David Starkey went on an extraordinary rant on Newsnight a few years ago about how “whites had become black” (i.e. were getting involved in street violence). No one is trying to ban him from talking to British universities.

The same students who tried to stop Julie Bindel from talking about free speech (the irony) at Manchester university this autumn did not simultaneously attack her fellow speaker Milo Yiannopolous, even though his views on transgender people are more extreme than hers. (He believes they are mentally ill and should be denied surgery.) Brendan O’Neill writes almost weekly on the Spectator website that transgender politics is “hocus pocus”. Where’s the NUS motion condemning him?

Exactly. Why is it women? Why is it feminist women? Why is it people who see themselves as progressives leading the charge?

It is ironic that this debate has focused around the idea of accepting trans women as women, because it also seems to me that we have a problem accepting non-trans women as fully human – a mixture of good and bad, wrong and right. Because, of course, Germaine Greer wasn’t even booked to talk about trans issues at Cardiff: the title of her lecture was “Women and Power in the 20th Century”. As with other feminists, it is assumed that her bad opinions on one subject render her persona non grata on everything else.

Tell me about it.

But in better news – she has an update at the end:

Cardiff University have been in touch to say they have subsequently spoken to Greer’s representatives, and the event is still scheduled to go ahead next month.

Good.