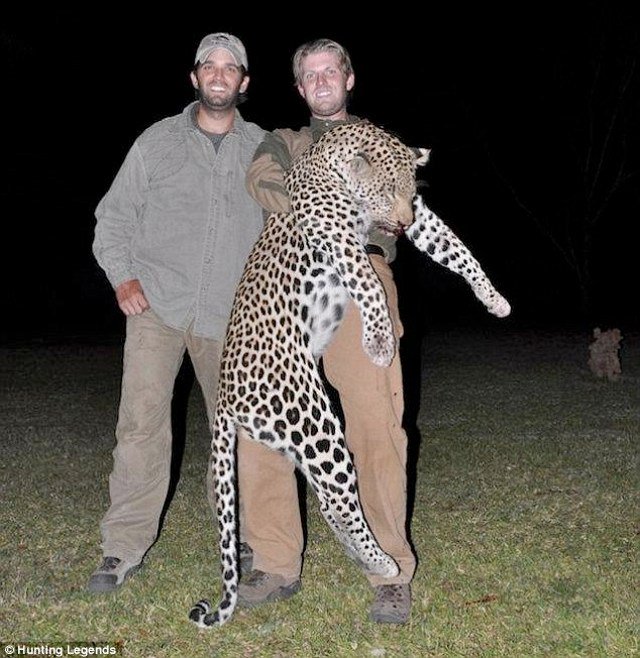

Meanwhile, as Trump burbles about nukes and crying babies and angry Muslims with thick accents, Obama writes a piece for Glamour about feminism.

He points out that it’s not just about changing laws, it’s about changing ourselves.

As far as we’ve come, all too often we are still boxed in by stereotypes about how men and women should behave. One of my heroines is Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, who was the first African American to run for a major party’s presidential nomination. She once said, “The emotional, sexual, and psychological stereotyping of females begins when the doctor says, ‘It’s a girl.’ ” We know that these stereotypes affect how girls see themselves starting at a very young age, making them feel that if they don’t look or act a certain way, they are somehow less worthy. In fact, gender stereotypes affect all of us, regardless of our gender, gender identity, or sexual orientation.

They’re probably the stereotypes that affect us all the most.

I also have to admit that when you’re the father of two daughters, you become even more aware of how gender stereotypes pervade our society. You see the subtle and not-so-subtle social cues transmitted through culture. You feel the enormous pressure girls are under to look and behave and even think a certain way.

And a lot of men are not aware of that.

We need to keep changing the attitude that raises our girls to be demure and our boys to be assertive, that criticizes our daughters for speaking out and our sons for shedding a tear. We need to keep changing the attitude that punishes women for their sexuality and rewards men for theirs.

We need to keep changing the attitude that permits the routine harassment of women, whether they’re walking down the street or daring to go online. We need to keep changing the attitude that teaches men to feel threatened by the presence and success of women.

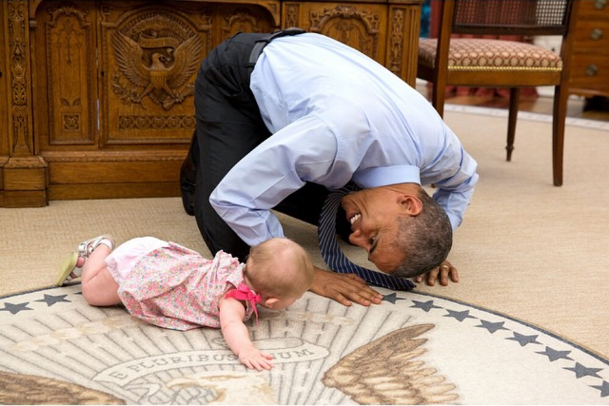

We need to keep changing the attitude that congratulates men for changing a diaper, stigmatizes full-time dads, and penalizes working mothers. We need to keep changing the attitude that values being confident, competitive, and ambitious in the workplace—unless you’re a woman. Then you’re being too bossy, and suddenly the very qualities you thought were necessary for success end up holding you back.

They are necessary for success, but all the same if you’re a woman you’re punished for them. You can’t win.

We need to keep changing a culture that shines a particularly unforgiving light on women and girls of color. Michelle has often spoken about this. Even after achieving success in her own right, she still held doubts; she had to worry about whether she looked the right way or was acting the right way—whether she was being too assertive or too “angry.”

Remember the 2008 campaign? Yup.

I can’t see Trump ever writing an article like this.