Shashank Bangali at the LA Times takes a look at the controversy over “Mother” Teresa.

Few people are as closely identified with a city as Mother Teresa is with Kolkata, the onetime colonial Indian capital where the Albanian nun garnered worldwide admiration for her work with the poor, infirm and outcast.

…

Many in Kolkata revere her for the half-century of service that earned her a Nobel Peace Prize and the moniker “saint of the gutters.” The Missionaries of Charity, the order she founded in 1950, sheltered tens of thousands of leprosy victims, sidewalk-dwellers, tuberculosis patients, orphans and the disabled at 19 homes across the city, and now has branches in 150 countries.

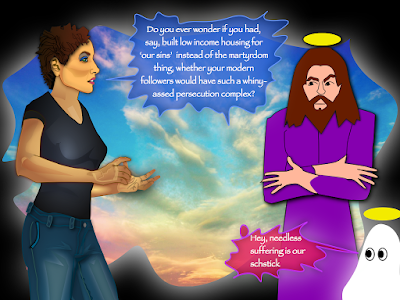

What exactly was her “work” with the poor, infirm and outcast? It wasn’t meeting the needs of the poor, infirm and outcast, it was trying to glorify the Catholic church through them. The missionaries “sheltered” leprosy victims, sidewalk-dwellers, tuberculosis patients, orphans and the disabled – but mere shelter isn’t enough (and it was crappy shelter). She had the money to do more but she gave it to the church.

“She had no significant impact on the poor of this city,” said Bikash Ranjan Bhattacharya, who served as mayor from 2005 to 2010.

“Whatever good work she did has also been done by any other philanthropic organization. I don’t find anything extraordinary in it.”

Bhattacharya is one of a few vocal critics in Kolkata who argue that Mother Teresa’s shelters glorified the ill rather than treating them, and that her charity appeals across the world misstated the reality of what was once among India’s most prosperous cities.

“No doubt there was poverty in Calcutta, but it was never a city of lepers and beggars, as Mother Teresa presented it,” Bhattacharya said.

“She was responsible for creating a negative image of this city. As a Calcuttan I feel totally disgusted by it.”

She put her hands on people, but she didn’t provide them with medical treatment.

“She would walk through the streets or go around in a wheelchair, speaking with everyone,” said Renu Sarnakar, a bespectacled woman in her 50s who was fashioning packets of Hindu religious offerings out of banana leaves. “Once she caressed my face very lovingly, even though I was ill.”

A widow, Sarnakar said she was admitted to Nirmal Hriday a decade ago with tuberculosis. Medical care was basic, and Sarnakar recalled that many in the women’s ward did not survive.

“The ones who die, they die,” Sarnakar said. “But for those who can get better, the sisters are very good to us.”

They die if they don’t get medical treatment. The nun could have spent the money to make that happen, but she gave it to the Vatican instead.

Mother Teresa faced criticism over the spartan conditions at Nirmal Hriday beginning in the early 1990s. The editor of the Lancet medical journal, Robin Fox, found after volunteering there that the sisters did not seek medical diagnoses for patients and administered only the most rudimentary painkillers and antibiotics.

The nuns resisted change, with Mother Teresa often saying that suffering brought one closer to God. A decade after her death, the nun then in charge of the home, Sister Glenda, told the local Telegraph newspaper, “We don’t want modern things.”

If they don’t want modern things, they should leave sick people alone.

In the fall of 2008, Hemley Gonzalez, a Cuban-born Miami real estate broker seeking a fresh start after the housing crash, came to Nirmal Hriday as a volunteer. He was tasked with giving daily sponge baths to 50 men, including some suffering from respiratory infections.

But there was no heating, making the water unbearably cold for the patients, Gonzalez said.

“The men started screaming when I poured water on them,” he said. “I’m not a doctor, I’m not a nurse, but I can tell by common sense that if someone has a respiratory disease you don’t bathe them with cold water.”

When Gonzalez proposed raising money for a water heater, senior nuns rebuffed him.

Gonzalez said the nuns did not distinguish between patients who were terminally ill and those who could be treated and released. He said he observed nuns rinsing dirty needles with tap water and reusing them.

“It felt like a museum of poverty,” said Gonzalez, 40, who later founded Responsible Charity, a nonprofit organization that promotes children’s education in Kolkata and the western city of Pune.

Hemley friended me on Facebook years ago, because I had a critical view of the Albanian nun.

Aroup Chatterjee, a Kolkata-born physician, said when he moved to Britain to practice medicine in the mid-1980s, Westerners told him constantly that his city “must be horrible, because that’s where Mother Teresa works.”

While Kolkata has vast pockets of poverty — three in 10 residents live in slums — it has lower income inequality and fewer underage workers than other major cities, according to official statistics, and the state’s per capita income is on par with the national average.

“It was very disturbing for me to hear that people thought that I came from a city and a culture that was so helpless that we couldn’t take care of ourselves, and we had to depend on an Albanian nun to look after our every need,” Chatterjee said.

In a 400-page book, recently rereleased under the title “Mother Teresa: The Untold Story,” Chatterjee levels an extensive list of complaints — including her embrace of unsavory donors (including savings and loan swindler Charles Keating) and allegations that she secretly converted Hindu and Muslim patients to Christianity on their deathbeds.

In a videotaped January 1992 meeting with the staff at Scripps Clinic in San Diego, where she had been treated for pneumonia, she boasted of baptizing as many as 29,000 people who had died at Nirmal Hriday since 1952.

“Not one has died without receiving the special ‘ticket for St. Peter,’ we call it,” she said. “It is so beautiful to see the people die with so much joy.”

Chatterjee said Indian officials should have raised concerns that the conversions violated the patients’ religious freedom, but such views remain unpopular.

We just won’t grow up, will we.