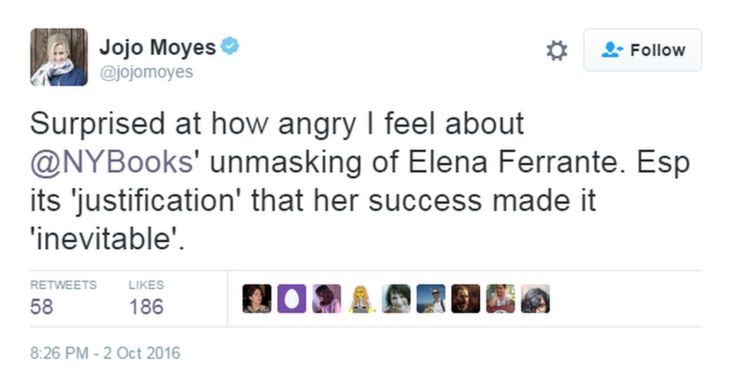

A wise and balanced Ferrante-take corrective by @NoreenMalone, which I agree with 95%:

and linked to Malone’s article, Elena Ferrante’s ‘Unmasking’ Wasn’t the End of the World.

Sigh. Yeah great, but nobody said it was the end of the world. Why do we have to be “balanced” about everything anyway? Why is “balance” necessary in this case? Why can’t we say authors have a right to be anonymous if they want to, and journalists have no duty or responsibility or obligation whatsoever to strip them of that right and that anonymity, and that it’s that much more ugly and domineering when it’s a man stripping a woman? Why is it “unbalanced” to say that?

Malone’s piece is annoyingly dismissive.

Gatti’s logic here is not exactly airtight, and does have an unfortunate whiff of “she was asking for it.” But Ferrante’s true biography had long been an object of interest in newspapers and magazines…Despite her anonymity, Ferrante has given plenty of interviews,especially recently. If the pseudonym allowed us to encounter her work in a specific way initially, the status of the work has changed in the last several years: Enormous success comes with burdens as well as benefits, but it certainly makes her identity more newsworthy than it was when she first started writing under a pseudonym.

What the hell does “newsworthy” mean? Other than “people are interested in it”? People are interested in lots of things that they have no right to know more about. Again: having a desire does not create a right to have that desire satisfied. I realize that’s a terribly “unbalanced” claim, but I’m sticking to it. Curiosity about other people is all but universal, but that doesn’t translate to some universal duty to make everything public. It doesn’t matter that Ferrante’s identity was “newsworthy”; it was still hers to keep to herself if she chose.

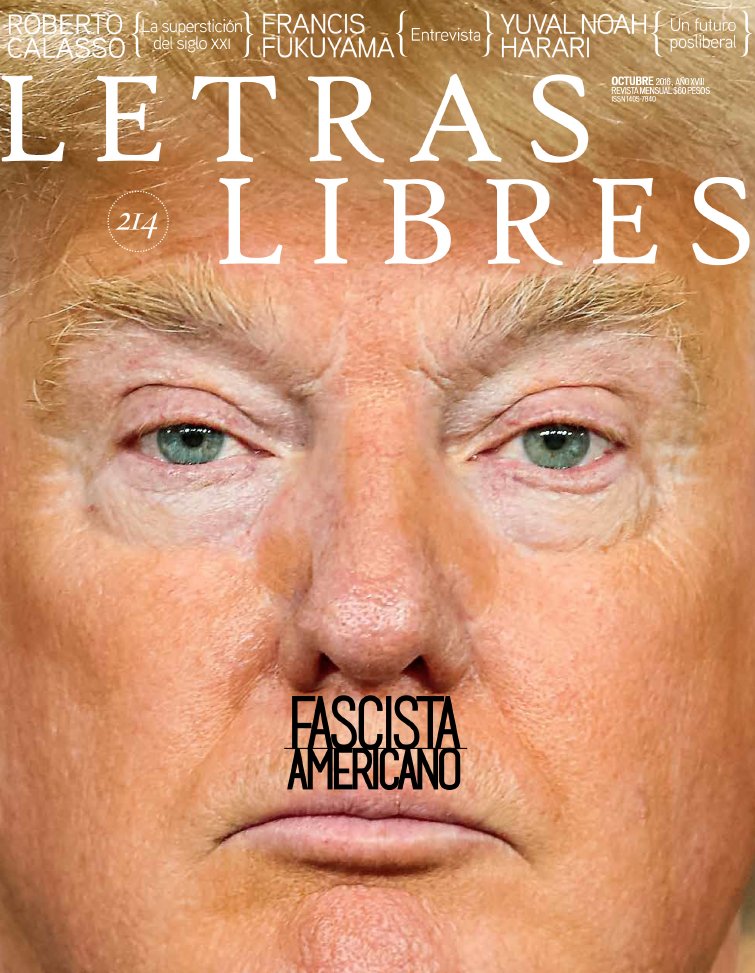

According to the current conventional wisdom, the exposé was a kind of emotional violence, both against the writer and the readers; further, goes this thinking, there is a particular roughness inherent to a male reporter unmasking a female author who has asked for privacy. The New Yorker’s Twitter account uses the language of consent: “In his apparent unmasking of Ferrante — the journalist does not explain why he felt free to take her ‘no’ as his ‘yes.’” As does Charlotte Shane, a writer and co-founder of TigerBee Press, who tweeted, “Leave it to a goddamn man to decide that the tremendous gift that is Elena Ferrante’s writing needs to repaid with senseless violation.” In The Guardian, Suzanne Moore writes that “those who love Ferrante’s work are appalled, partly of course because she writes so well about the ways in which men humiliate women.”

How is that “the conventional wisdom”? Yes a lot of us thought it and said it, but that doesn’t make it the conventional wisdom. I’m not sure it’s particularly “balanced” of Malone to call it that.

It is true that, thanks to the searing portrait of male cruelty her novels paint, the mere mention of Ferrante’s name might get many of us in the mood to discuss a generalized terribleness of men. And yet this all seems to me both an almost-insulting underestimation of the fortitude of the author, and a severe overestimation of the harm that might be done by connecting universally praised work to its actual creator.

That’s not your decision to make. It’s not ours. It certainly isn’t Claudio Gatti’s. It’s not anyone’s but Ferrante’s. “Consent,” anyone? I don’t find Malone’s callous dismissal the least bit “balanced”; I think it’s quite warped.