Montgomery

If we wanted to have a white supremacy museum, where would we put it? Montgomery, Alabama would be a good choice.

It was at the statehouse in Montgomery that Jefferson Davis was first inaugurated as the president of the Confederacy in a bid to preserve the institution of slavery and in defense of the inferiority of the black race. It was here too, nearly a century later, that Rosa Parks famously refused to give up her seat, and a young Martin Luther King launched his first direct action campaign: The Montgomery Bus Boycott.

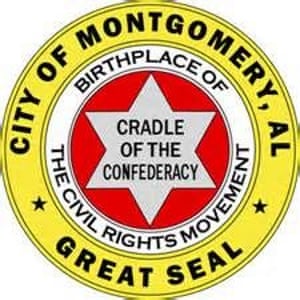

Indeed the official city seal tells some of this story in ironic juxtaposition, nesting its claim as “Cradle of the Confederacy” inside that of “Birthplace of the Civil Rights Movement”.

That is truly bizarre.

Montgomery was also for a time the central hub of the domestic US slave trade, and that’s part of why writer and activist Bryan Stevenson thinks is a perfect place for a “new kind of museum” entitled From Slavery to Mass Incarceration that will that will trace the untoward history of racial capital through generations and simultaneously shine a light on the legacy of US racial terrorism.

“It all begins with enslavement and the ideology of white supremacy and what follows is lynching, segregation, and many of the issues that we’re dealing with today,” Stevenson told the Guardian.

The museum itself will be situated at the site of a building that once warehoused enslaved people before they could be sold auction in the town square. “They used it for livestock, cotton and enslaved people,” Stevenson said.

…

“By 1860, warehouses, slave depots, and slave pens had sprung up all over the city of Montgomery. We had more slave pens, depots, and warehouses than banks, hotels, or commercial establishments,” said Stevenson, the executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative which is headquartered in Montgomery and is spearheading the project.

Places to store and sell human beings. This is our history, just a century and a half ago – and still, if you look at mass incarceration as an offshoot of slavery.

The museum space, beyond slavery and lynching will also cover the rise of lend-lease, the practice by which many formerly enslaved blacks were resubjugated. Many Southern municipalities adopted nuisance laws that could legally detain blacks for no crime at all, and sentence them to hard labor as punishment. This, EJI argues, draws a direct line to the explosive rise in the US prison population through the later part of the 20th century that has become known as Mass Incarceration, and how it has preyed on communities of color.

This arc, from slavery through these more modern iterations of racial inequality speaks to the museum’s core mission. Rather than a focus on historical artifacts, Stevenson said the project intends to walk visitors through a comprehensive narrative of US racism. Drawing inspiration from the Apartheid museum in South Africa, which is similarly conceived, Stevenson said that the museum starts with a point of view, and one that he believes is necessary to amplify if the nation is ever to push meaningfully past its foundational racist demons.

“I do think our nation is a nation that needs truth and reconciliation, and incidents like Charleston and Charlottesville just reinforce that,” Stevenson said, but added that truth and reconciliation is not simultaneous, it’s sequential.

“You have to tell the truth before you can get to reconciliation, and culturally we have done a terrible job of truth telling in this country about our history of racial inequality. I see these projects as an effort to respond to the absence of truth and the silence that has haunted us – black, white and other – for too long.”

Some documentaries on the subject would be an idea too.

They have historic markers around town (I live in Montgomery). It was only recently that the government was persuaded to allow markers talking about slavery. The tourism efforts promote both the Civil War history and historic events of the civil rights movement, lumping them together under the bizarre banner of “Civil History”.

I am eager to see what EJI puts together. I think it’s important. The idea seems controversial, too “negative”, even among people who I thought would be enthusiastic supporters.

I think that the museum is a wonderful idea – provided that there is no “We’re sorry about slavery, but…” going on. Which means, I suppose, that first of all any signs around the town putting a positive spin on the insurgency have to be changed.

Do they see it as “controversial” in its entirety? Or is it just the mass incarceration part?

The “controversial” aspect seems to be that some people are tired of so many exhibits commemorating awful things. I’m mostly recalling some discussions about the lynching memorial among a group of social justice activists I know. I haven’t heard anything about it in a while, so maybe they grasp the concept better now?